Solvable Quantum Models

Contents

3. Solvable Quantum Models¶

Solving the Schrodinger equation for different quantum systems, we essentially add different choices of potential \(V({\bf x},\,t)\). In each case the Hamilonian operator:

will vary depending on the choice of potential.

3.1. Bohr Model¶

This one is a bit of a cheat, because solving it does not involve the Schroodinger equation, however it does allow us to address some conceptual ideas in quantum theory. To do this properly, we need to consider the hydrogen atom properly, which we do in a later section. The basic idea of the Bohr model, starting with Hydrogen, is to assume that electrons are in circular motion around the nucleus:

which is equal to the Coulombic attraction between the electron \(-e\) and proton \(+e\):

Thus we find the velocity of these bound electrons is found by:

The kinetic energy of these electrons is given by:

Where the \(-\) sign is introduced since these electrons are bound and we would need to give \(E = \frac{1}{2}m_e\,v^2\) worth of energy for the electron to be free with net zero energy. Notice that since \(E_K \propto \frac{1}{r}\), this formally happens as \(r \rightarrow \infty\). Bohr’s key insight was that the electrons do not orbit the atomic nucleus akin to planets around a star, but instead behave as electron matter waves. Electrons have a de Broglie wavelength:

then the key idea here is that different orbits around the nucleus would correspond to different wavelengths, with only complete wavelengths are permitted. The circumference of each orbit would be:

this means the angular momentum \(L = m\,v\,r\) is given by:

Substituting in the expression for \(v\) allows us to write the allowed radius of orbits:

and hence the energy of the electrons is found to be:

where the coefficients are collected together as the Rydeburg energy \(R_E \simeq 13.6 eV\). Recall that electron volts, eV,

represent the amount of energy given to a particle with charge of \(e = 1.6\times 10^{-19}\) C travelling across a potential

difference of 1 V. This expression suggests electrons can move between energy levels, e.g. the energy emitted moving from

the \(n_1\) to \(n_2\) energy level would be:

The typical size of an atom can be represented by the ground state radius, \(r_{n=1}\), which is denoted by \(a_0\) and known as the Bohr radius:

We stress that this result is semi-classical, it has its limitations and does not correctly account for additional quantum effects. One obvious issue is how to generalise this expression to larger atoms, initially the most obvious thing to do is adjust the size of the atomic nuclear:

where \(Z\) is the atomic number of the element in question. The biggest issue with this approximation is that it leaves out the \(e-e\) interactions within each energy level, something which is not typically present in atomic Hydrogen.

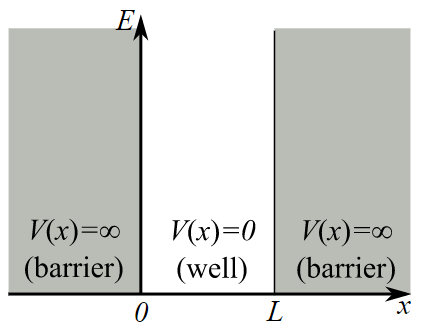

3.2. Infinite Square Well¶

One of the simplest quantum systems we can investigate is the infinite square well, where the potential energy of the system traps the wave function within a well, as shown in Fig. 6.1.

Fig. 3.1 The infinite square well system¶

To solve the Schrodinger equation for this system:

we can start by using a separable ansatz:

and therefore drop the partial derivatives and set the problem up as two ODE problems with eigenvalues \(E\):

Inside the well, \(V = 0\) which simplifies the \(x\) ODE further:

and therefore has solutions:

At the boundaries of the well, \(x = 0,\,L\), we find an infinite potential \(V\) which is usually problematic for a physical system, however if we make \(\Psi(0,t) = \Psi(L,t) = 0\), then this can be fixed and this gives us the relevant boundary conditions:

and hence

which means that there are energies \(E\) of the form:

and the expressions for the different wave function solutions are given by:

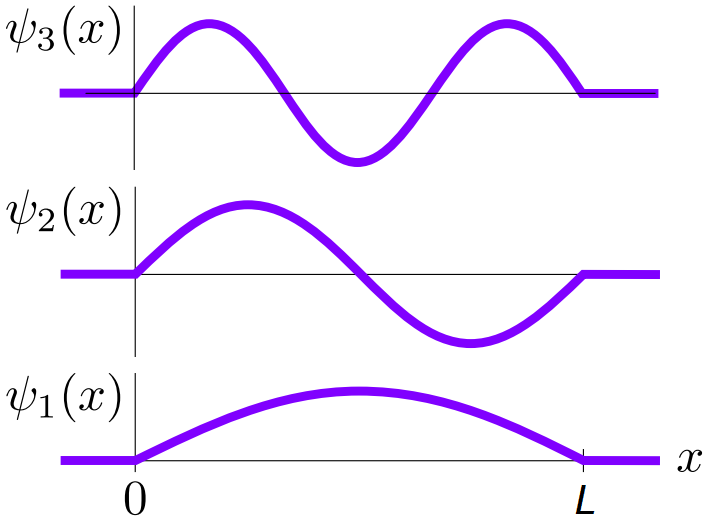

and we can plot these as shown in Fig. 6.2

Fig. 3.2 Wave functions for the infinite square well for the first three energy levels.¶

We see that this system is simply just the standing wave system with the string fixed at both ends! Rearranging we see that \(L = n \lambda/2, \,n \in \mathbb{N}\). The temporal ODE is of the form:

which has solution:

where we found the form of \(E_n\) from the spatial solutions, therefore the full wave function solutions are:

We can find \(A'\) from the necessity that wave functions are normalised, since

to make the function a probability distribution, that would fix:

Making use of the double angle formula \(\cos(2A) = 1 -2\sin^2(A)\) to make the integration doable, we find:

and therefore the wavefunction over all space is given by:

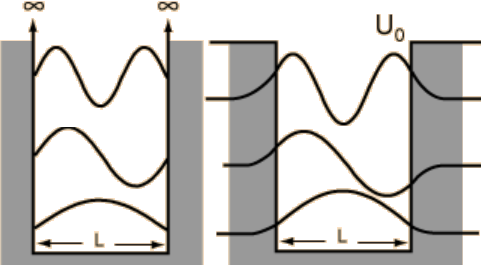

3.3. Finite Square Well¶

If the system now has a finite square well, \(V = U_0\), then is possible to have wavefunction solutions outside of \(0 \leq x \leq L\), lets consider the Schrodinger equation again:

which for lower energy solutions \(E < U_0\) means that:

which can be solved to find:

since we do not find wave functions growing as \(x \rightarrow \infty\), \(B = 0\), meaning that

which are exponentially decaying solutions - this is quantum tunnelling! We can see a pictorial representation of these finite well solutions alongside the infinite well solutions in Fig. 6.3. To find exact expressions for the wave functions in the finite well case is not so easy however, as \(\Psi(x,\,t)\) is expected to be continuous.

Fig. 3.3 Infinite (left pane) and finite (right pane) square well wave functions.¶

3.4. Quantum Harmonic Oscillator¶

This system is the quantum analogue of the classical simple harmonic oscillator, the Hamiltonian is given by:

We can solve this system to find wave-functions of the form

Where the functions \(H_n\) are known as Hermite polynomials, which satisfy:

The corresponding energy levels for this system are:

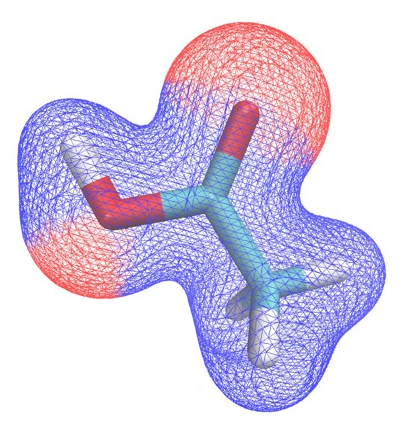

3.5. Revisiting the Hydrogen Atom¶

We can put in a Coulomb law’s potential into the TISE as a model for the Hydrogen atom, this gives:

where \(\mu\) is the {\it reduced mass} of the system, which takes into account the slight influence of the electron mass \(m_e\) on the proton mass \(M_p\), the centre of mass of the system is shifted slightly:

If we expand the Laplacian \(\nabla^2\) in spherical polar coordinates, this produces a PDE:

which turns out to be separable using the ansatz:

which reduces the PDE into three ODE’s:

where \(A,\,B\) are the separation constants for this system. This system can be solved using a combination of integrating factor for the \(R(r)\) functions and Spherical Harmonics for \(\Theta(\theta),\,\Phi(\varphi)\), which are complete functions that can be used to decompose the surface of a sphere. The overall solutions are:

Where the radial coordinate \(r\) is best represented by a dimensionless parameter \(\rho\):

and the parameter \({a_0}^{*}\) is known as the reduced Bohr radius:

taking into account the reduced mass \(\mu\).

The function \({L_{n-\ell -1}}^{2\ell +1}(\rho )\) is a generalized Laguerre polynomial of degree \( n-\ell -1\), and the function

\(Y_{\ell}^{m}(\theta,\,\varphi)\) is a spherical harmonic function of degree \(\ell\) and order \(m\). The parameters \(\ell,\,m,\,n\)

are known as quantum numbers and can take the following values:

\( n = 1,2,3,\ldots \) this is known as the principal quantum number.

\( \ell = 0,1,2,\ldots ,n-1 \) this is known as the azimuthal quantum number.

\( m = -\ell ,\ldots ,\ell \) this is known as the magnetic quantum number.

Additionally, the wave-functions are both normalized and orthogonal:

3.6. A note on units¶

It is usually easier to use atomic units when considering the computing systems, this saves memory storing excessively large or small values and only converting values at the end, In Hartree atomic units, we set \(\hbar = m_e = a_0 = e = 1\) and energies measured in atomic units can be converted into electron volts using the Hartree energy:

If we consider the Hydrogen atom Hamiltonian: