Binomial Expansion and Theorem

Contents

2. Binomial Expansion and Theorem¶

Throughout your scientific journey you will likely come across a time where you have to solve an equation like \((x+y)^n\). We will know describe how you go about such a task and will highlight some interesting mathematical relations.

2.1. Definition of a binomial¶

Polynomials are expressions such as \(a_0 + a_1 x + a_2 x^2 + a_3 x^3\) where \(a_0,\ a_1,\ a_2,\, a_3\) are the polynomial coefficients and \(x\) is the variable. They can have multiple variables (e.g. \(x\) and \(y\)) such as \(a_0 + a_1 x + a_2 x y + a_3 x y^2\).

A binomial is a polynomial with two terms (e.g. \(x + y, x^3 + 1, 4.3 x^5 - 2.2 y\), etc).

The binomial expansionrefers to the computation of powers of binomials:

Equation (2.1) is a general way to express a binomial expansion - the expansion of more complicated binomials can consider by “swapping in” other functions for the \(x\) and \(y\) (e.g. \(x\to 10 x^3\) and \(y \to \sqrt{17} e^x\)). In this section we will investigate the binomial expansion only for the case where \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

2.2. The binomial formula¶

We now set out to calculate the polynomials produced by the expansion of powers of a binomial.

2.2.1. Expanding low powers of binomials by hand¶

It is possible to expand low powers of binomials (i.e. \(n=0,1,2,3,4,5\)), equation (2.1), by hand:

You can see symmetry and patterns in the polynomials on the right hand side of the expansions. For instance, the combined powers of the \(x\)’s and \(y\)’s are equal to the power of expansion \(n\) and the total number of terms is \(n+1\). But what is the pattern for the coefficients?

The answer to this is not trivial and is a fundamental sequence of numbers - the binomial coefficients.

The binomial coefficient

The binomial coefficent is defined as:

where \(n \in \mathbb{N} \) and \( 0 \leq k \neq n, \, k \in \mathbb{N}\).

Questions

Can you prove the following facts about the binomial coefficients?

Hint: use the definition of the binomial coefficent.

Solutions

Starting by writing out the result for the right hand side of the first expression gives

The second expression follows directly from the definition of \(\displaystyle \binom{n}{k}\).

Like the number \(\pi\), the binomial coefficient pops up in many unexpected places - particularly in counting problems (the bread-and-butter of the field of combinatorics). The binomial coefficient is the number of ways, disregarding order, that \(k\) objects can be chosen from \(n\) objects. This number \(\binom{n}{k}\) can be casually referred to as “n choose k”, and can be expressed by \(C^n_k\) and hence calculators encode the binomial coefficient by the “\(_n C _k\)” button.

2.2.2. Pascal’s triangle¶

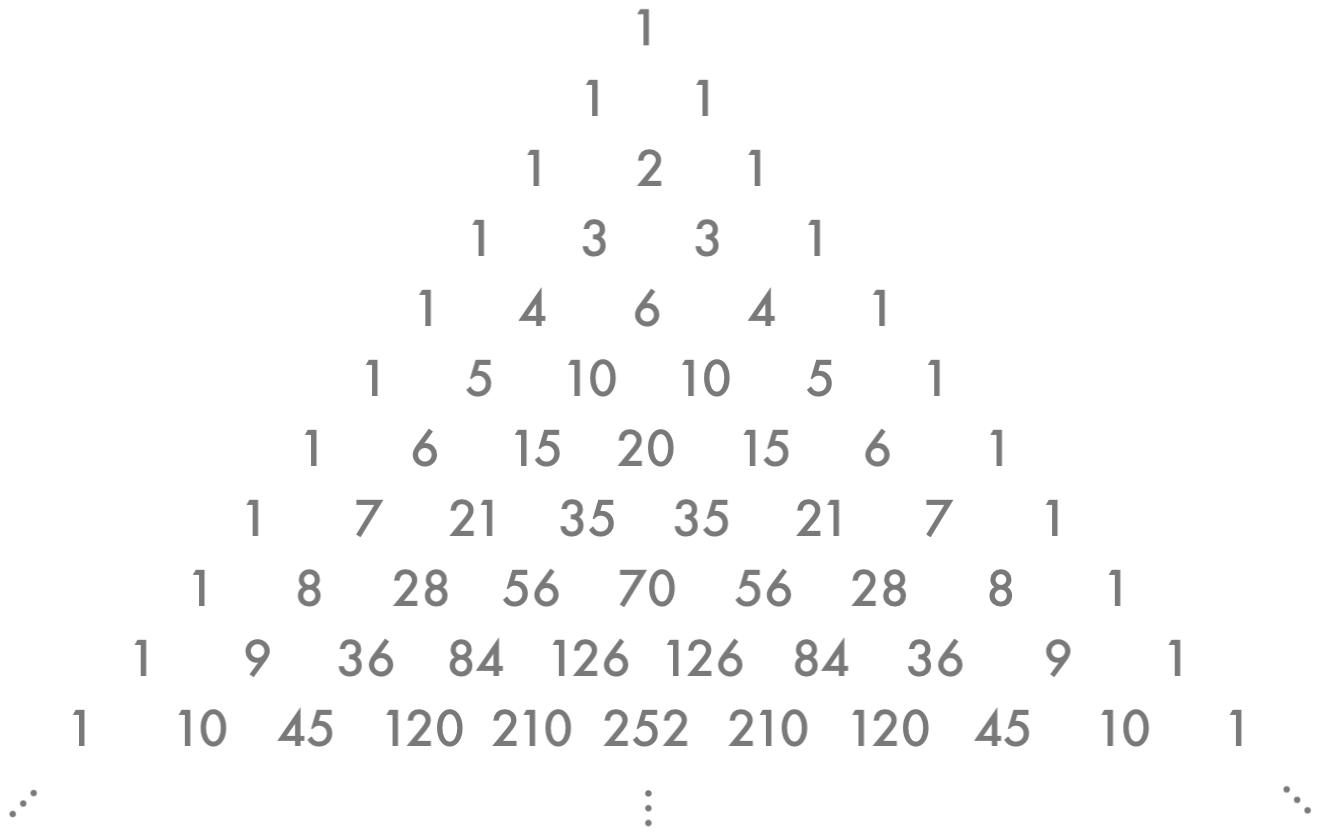

A very old (it is thought first discovered in 115h century China), but very elegant, way of calculating the binomial coefficients (equation (2.2)) can be found using Pascal’s triangle.

The binomial coefficients have a recurrence relation hidden within them:

This follows from the adding of related terms in Pascal’s triangle:

Fig. 2.1 Pascal’s triangle: a table of binomial coefficients \(\displaystyle \binom{n}{k}\).¶

In Pascal’s triangle the left-most and right-most values are initially filled out according to the result \(\displaystyle \binom{n}{0} = \binom{n}{n} = 1\). Then, the recursive formula \(\displaystyle \binom{n+1}{k} = \binom{n}{k} + \binom{n}{k-1}\) is used to fill out the rest of each row. The trick is that each value is calculated by adding the two values from the row above that are in the same column and the preceding column.

Pascal’s triangle provides a quick way of finding binomial coefficients by hand. For instance, to compute the expansion of \((x+y)^6\), we can read off the coefficients from the 6th row in Pascal’s triangle:

2.2.3. Factorials¶

We briefly note that the “\(!\)” symbol represents a factorial of an integer. A factorial of integer number \(n\) is defined as the product of all the numbers from \(1\) to \(n\):

There is also a special case of factorials \(0!=1\) - this might seem unintiutive, but it follows from the reurrence relation

The special cases of the binomial coefficient (equation (2.2)) are thus \(\binom{n}{0}= 1\), \(\binom{n}{1} = n\), \(\binom{n}{n}=1\) and \(\binom{n}{n-1} = n\).

These examples highlight a nice symmetrical property of the binomial coefficient: \(\binom{n}{k} = \binom{n}{n-k}\) (where \(0 \le k \le n\)).

2.2.4. Statement of the binomial formula¶

The binomial formula

The binomial formula (otherwise known as the binomial theorem) is defined as:

You are not required to be familiar with the details of its derivation but do need to be able to apply the formula to compute binomial expansions. This formula also shows you why \(\displaystyle \binom{n}{k}\) are called binomial coefficients - because they are the coefficients of the polynomial produced by the expansion of powers of binomials.

Questions

1. Calculate \((x+y)^9\) using the binomial theorem.

2. Calculate the coefficient of the \(x^2 y^3\) term in the expansion \((2 x - 3)^5\).

3. Expand \((1+x-x^2)^7\) in ascending powers of \(x\) up to and including the term in \(x^3\).

Solutions

1.

2. The term in \(x^2 y^3\) is given by

hence the coefficient is \(-1080\).

3.