30. Conservation law derivations¶

In this section:

What is measured by the material derivative?

What do the terms in the mass and momentum conservation equations mean?

30.1. The material derivative¶

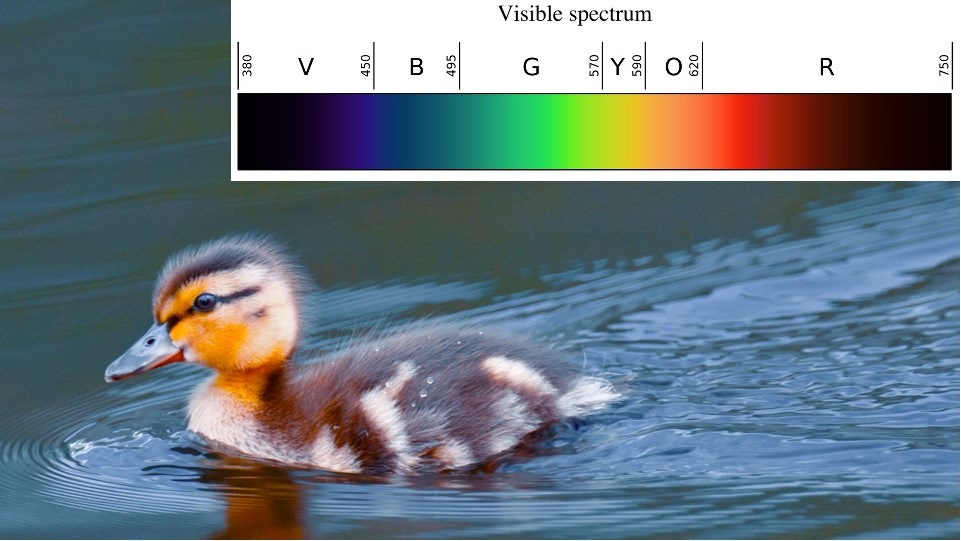

In Section 26.3 (The directional derivative) we found that the rate of change of a steady (time-independent) field \(\phi(x,y,z)\) in a given direction \(\underline{u}\) can be found by a scalar projection:

Now, suppose that the background field is non-steady, so that \(\phi=\phi(\underline{x},t)\). Proceeding as before by using the multi-variate chain rule, we immediately obtain

This result is called the “material derivative” or “convective derivative”, and the notation \(\mathrm{D}/\mathrm{D}t\) is used in place of the ordinary derivative to signify its special significance. The first term accounts for the temporal evolution of the background field, and the second term (convection term) accounts for changes as a consequence of moving through the field with velocity \(\underline{u}.\)

The material derivative can also be applied to each element of a vector field \(\underline{\phi}\), to give the change in \(\underline{\phi}\) following the motion of a fluid particle. For example \(\frac{\mathrm{D}\underline{u}}{\mathrm{D}t}\) gives the convective acceleration.

Exercise 30.1

Write out the convective acceleration \(\frac{\mathrm{D}\underline{u}}{\mathrm{D}t}\) in component form, taking \(\underline{x}=(x,y,z)\) and \(\underline{u}(t,\underline{x})=(u,v,w)\).

We have \(\underline{u}.\nabla = u\frac{\partial}{\partial x}+v\frac{\partial}{\partial y}+w\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\)

Hence, \(\frac{D\underline{u}}{Dt}=\frac{\partial\underline{u}}{\partial t}+\underline{u}.\nabla\underline{u}=\begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial u }{\partial t}+u\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+v\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}+w\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\\ \frac{\partial v }{\partial t}+u\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}+v\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}+w\frac{\partial v}{\partial z}\\ \frac{\partial w }{\partial t}+u\frac{\partial w}{\partial x}+v\frac{\partial w}{\partial y}+w\frac{\partial w}{\partial z} \end{pmatrix}\)

30.2. Mass transport (continuity)¶

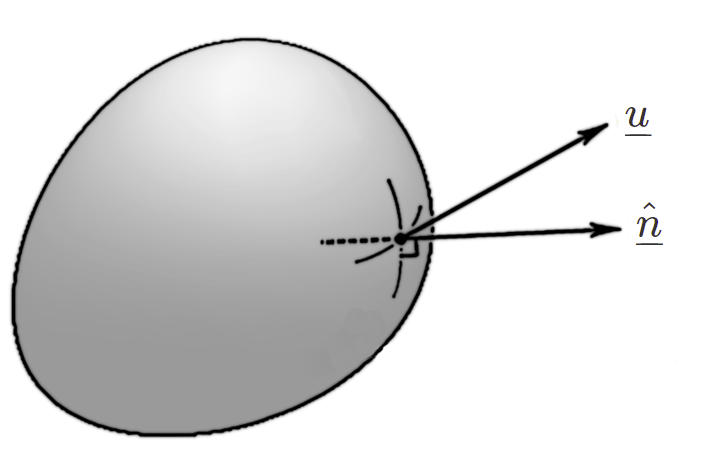

Consider the mass flow through an arbitrary volume at a fixed location, like the “bag” shown in the image on the left. We assume matter is neither created or destroyed.

The following statement says that the change in mass of the fluid parcel is equal to the net mass flow into the enclosing surface \(\delta A\) per unit time.

The negative sign appearing in the formula occurs because the normal direction is outward from the surface, as illustrated in the image.

The time derivative on the left hand side of equation (30.2) can be brought inside the integral because for a fixed fluid volume the spatial and temporal variables are independent. On the right hand side the divergence theorem can be used to write the surface integral as a volume integral. Bringing all terms over to the left then gives

and since the volume \(\delta V\) is arbitrary this requires that the integrand itself is zero. By using the product rule to expand the intergrand, we can finally obtain

Important case: Mass transport for incompressible flow

If the density of each fluid particle does not change as it moves around, then the flow is said to be incompressible. In that case, \(\frac{D\rho}{D t}=0\), which leads to the following condition for incompressible flow :

In practice, fluid phenomena that are well below the speed of sound can be treated as incompressible

Exercise 30.2

a). Write down the continuity equation for compressible flow in component form, taking \(\underline{x}=(x,y,z)\), \(p=p(t,\underline{x})\) and \(\underline{u}(t,\underline{x})=(u,v,w)\).

b). What single equation can be used to model a flow that is both incompressible and irrotational?

c). Is incompressible flow the same as solenoidal flow?

a). \(\frac{\partial \rho }{\partial t}+u\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial x}+v\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial y}+w\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial z}+\rho \left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\right)=0\)

b). Laplace’s equation, \(\nabla^2\phi=0\), where \(\underline{u}=\nabla\phi\)

c). The condition for both types of flow is the same. Since incompressible flows must satisfy \(\nabla.\underline{u}\), they are solenoidal. However, it may be possible for a compressible fluid to exhibit solenoidal flow.

30.3. Cauchy stress theorem¶

“Stress” is a measure of the internal forces, such as pressure or friction acting between neighbouring fluid elements. We cannot discuss stress without first defining a particular surface that the stress acts on, since friction and pressure depend on the surface orientation.

However, the stress for a given surface can be expressed as a vector of components parallel to each coordinate direction, and according to Cauchy’s stress theorem, the stress vector on any plane through a point can be found by knowing the stress vector on each of three mutually perpendicular planes. We will consider planes perpendicular to the coordinate axes.

The Cauchy stress tensor (deviatoric stress tensor)

defines the normal and shear stress components \(\sigma_{i,j}\) acting on a plane perpendicular to each axis, as illustrated below:

We now consider the stress vector \(\underline{T}^{(\underline{n})}\) acting on an arbitrary surface \(\delta{A}\) perpendicular to unit vector \(\hat{\underline{n}}\) as illustrated in the figure below.

We may apply Newton’s second law to the tetrahedron shown, allowing the mass of the tetrahedron to approach zero (so that the sum of the forces also approaches zero):

where \(\delta A_j\) is the projection of \(\delta A\) onto the illustrated face, given by \(\delta A_j=\hat{\underline{n}}.\underline{e}_j\delta A=\hat{\underline{n}}_j\delta A.\)

This gives

30.4. Conservation of momentum¶

By Newton’s second law, the change in momentum is given by the sum of all forces acting on the volume:

in which

\(\rho\underline{F}\) is the “body force” per unit volume, such as gravitational, magnetic or Coriolis* forces

\(\underline{\sigma}(t,\underline{x}).\hat{\underline{n}}\) is the deviatoric stress tensor.

This time, we have to choose a “material volume”, meaning one that moves with the fluid, so that we track the same particles. In that case \(\rho\mathrm{d}V\) is constant so we may rewrite the left-hand side as

We use the divergence theorem again on the last term, and combine the three integrals for our arbitrary material volume \(\delta V\) to obtain

The Cauchy stress tensor \(\underline{\sigma}\) can be split up to separate normal stress components (pressure) and shear stress components. This gives the result

The negative sign is chosen due to the fact that the pressure acts inwards on a material volume.

Exercise 30.3

If we assume that the shear stress component is zero so that \(\underline{\tau}\equiv \underline{0}\) in equation (30.11), then we obtain the Euler equation

Write out this equation in component form for a Cartesian system under a body force \(\underline{F}=(0,0,-g)\).

The implications of ignoring the shear stress components will be explored in later sections of these notes.

*A physical derivation of the Coriolis force is outlined in the (optional) section of the notes on rotational reference frames.