9. Standing Waves¶

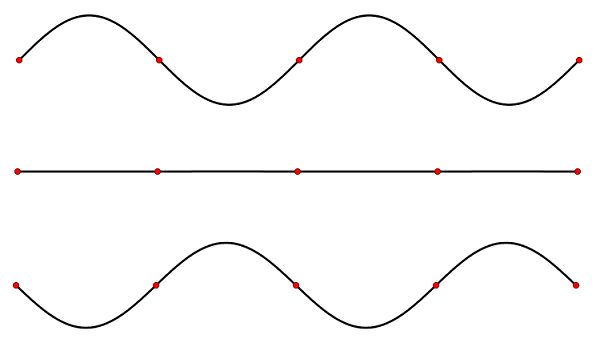

A standing wave, sometimes called a stationary wave, is a wave that remains in a constant position, as seen in Fig. 9.1. This can occur because in a stationary medium, two waves are traveling in opposite directions and end up interfering with each other or the medium is moving in the opposite direction to the wave.

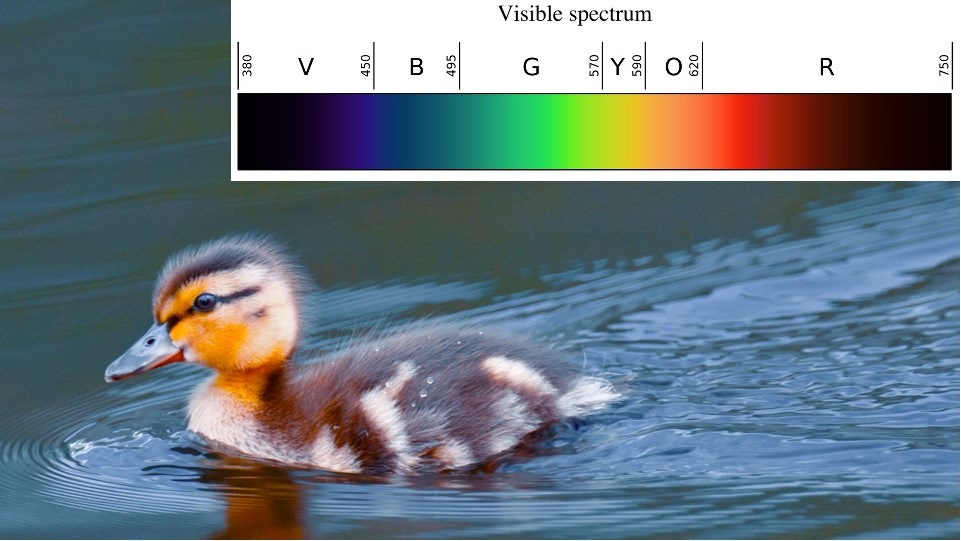

Fig. 9.1 A closed standing wave on a string, with pattern oscillating back and forth between the top, middle and bottom panels. We identify nodes, i.e. points that remain stationary, with points along the string.¶

Standing waves can arise when some kind of boundary blocks waves propagating and this causes the wave to get reflected and now there are two waves moving in opposite directions in the same domain. At either end of the wave domain, the two opposed waves are in anti-phase and cancel each other, producing a node. Halfway between two nodes there is an anti-node, where the two opposite directed waves constructively interfere. For standing waves, there is no net propagation of energy over time - it is all confined within the wave domain.

To describe a standing wave over a closed length \(L\), with boundary conditions:

so we find by summing left and right moving waves:

To solve this second condition, given the cyclic symmetry of \(\sin(kL)\), we will have:

We can also consider this from the phase shift as well, as a half wavelength \(\lambda/2\) corresponds to a phase of \(\pi\), for a full wavelength \(\lambda\), the phase is \(2\pi\) etc, hence we get \(k = 2 \pi/\lambda\) for the whole wave and then later solve for \(\lambda(L)\).

Thus for positive solutions, we find distinct harmonics (or notes) emerge:

and we can rewrite each notes wavelength \(\lambda\) in terms of the boundary size \(L\):

Similar considerations can also apply to a standing wave that is closed at one end and open at the other, which will have different boundary conditions.

It is clear that different values of \(x\) correspond to maxima, where the argument of \(u(x,\,t)\) will be odd multiples of \(\pi/2\):

these are the anti-nodes of the standing waves, located at \(x \geq 0\):

Equally we can find values of \(x\) where there are minima, the argument of \(u(x,\,t)\) will be even multiples of \(\pi/2\):

these are the nodes of the standing waves, located at \(x \geq 0\):