Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Contents

20. Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors#

20.1. Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors#

In this section we will study on of the most important concepts in linear algebra.

Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Let \(A\) be a square matrix, \(v\) a non-zero vector and \(\lambda\) a real number such that

Then \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue and \(v\) is an eigenvector of the matrix \(A\).

‘Eigen’ is a German word which roughly translates into English as ‘self’ or ‘own’. An eigenvector is a vector which is transformed to a multiple of itself by the matrix \(A\).

It is not obvious how to calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a given matrix, and this is a problem we will return to later. However, it is easy to check whether a given vector is an eigenvector simply by applying the definition.

Example

Show that \(v = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) is an eigenvector of the matrix \(A = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 2 \\ -4 & 8 \end{pmatrix}\) and calculate its corresponding eigenvalue.

Answer

Therefore, \(v\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) with eigenvalue \(\lambda = 4\).

Attention

Eigenvectors and eigenvalues are only defined for square matrices.

Eigenvectors are never zero but eigenvalues may be zero.

Exercise 20.1

Let the matrix \(A = \begin{pmatrix}0 & 6 & 8 \\ \frac{1}{2} & 0 &0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{2} & 0\end{pmatrix}\) and vectors \(v_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 16 \\ 4 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\), \(v_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 2 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix}\).

Which of \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) is an eigenvector of \(A\)?

Determine its corresponding eigenvalue.

20.2. Eigenspaces#

If \(v\) is an eigenvector of \(A\), it is easy to show that any scalar multiple \(cv\) is also an eigenvector:

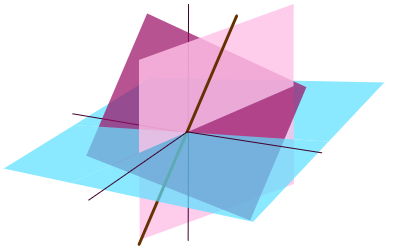

Thus, geometrically we can picture an eigenvector as a straight line through the origin that is left unchanged by the linear transformation corresponding to the matrix.

Definition

Let \(A\) be a square matrix and \(\lambda\) an eigenvalue of \(A\). Then the eigenspace of \(A\) corresponding to eigenvalue \(\lambda\) is the set of vectors \(v\) such that

Example

Determine the eigenvalues and corresponding eigenspaces of a \(\times 3\) dilation (scaling).

Solution

A \(\times 3\) dilation transforms each vector \(x\in \mathbb{R}^n\) to \(3x\). Therefore every nonzero vector is an eigenvector with eigenvalue \(3\).

Therefore \(A\) has a single eigenvalue \(\lambda = 3\) with eigenspace \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Note that this is true regardless of the value of \(n\)!

20.2.1. Calculating Eigenspaces#

We have seen how to check if a given vector is an eigenvector of a square matrix \(A\). It is then easy to find its corresponding eigenvalue.

Next we will learn how can to check whether a given real number is an eigenvalue of \(A\) and to find its corresponding eigenvector. This is slightly more complicated because there may be multiple eigenvectors corresponding to a single eigenvalue.

Now suppose \(A\) is an (\(n \times n\)) square matrix and \(\lambda\) a real number. If \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue then there exists a non-zero vector \(v\) which solves the following equation:

We would like to solve this for \(v\). To see how this is possible, let’s first examine a concrete example.

Example

Suppose we have an eigenvalue \(\lambda\) of the matrix \(A = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4 \end{pmatrix}\). Then an eigenvector of \(A\) is a non-zero vector \(v = \begin{pmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \end{pmatrix}\) which satisfies

This translates to the linear system of equations

which is the same as the matrix equation

Thus, introducing the identity matrix \(I\) allows us to rearrange (20.1):

Remember that this is an equation of vectors so the \(0\) on the right hand side is a zero vector of length \(n\).

Notice that this equation is of the form matrix times vector equals vector - and we already know how to solve such an equation, for example by using row reduction. If any solutions exist then they are eigenvectors of \(A\) and \(\lambda\) a corresponding eigenvalue.

Calculating Eigenvectors

Given a square matrix \(A\) and real number \(\lambda\), If

has non-trivial solutions then \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) and the general solution is the eigenspace of \(A\) corresponding to \(\lambda\).

Example

For each of the numbers \(λ = 1, 3\), decide if \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of the matrix

and calculate the corresponding eigenspace.

Answer

\(\lambda = 1\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) if the equation \(\left(A - I\right)v = 0\) has non-zero solutions.

\(A - I\) has determinant \(6\) and is therefore invertible and \(\mathrm{Nul}\left(A-I\right) = 0\).

Therefore there are no non-zero solutions to \(\left(A - I\right)v = 0\) and we conclude that \(1\) is not an eigenvalue of \(A\).

\(\lambda = 3\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) if the equation \(\left(A - 3I\right)v = 0\) has non-zero solutions.

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

and the general solution to \(\left(A - 3I\right)v=0\) is

Therefore \(\lambda = 3\) is an eigenvalue with corresponding eigenvector \(v = \begin{pmatrix}-4 \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\).

Exercise 20.2

Show that \(\lambda=-2\) is an eigenvalue of the matrix (20.2) and calculate its eigenvector.

20.3. The Characteristic Polynomial#

In the previous section we discussed how to decide whether a given number \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of a matrix, and if so, how to find all of the associated eigenvectors. In this section, we will give a method for computing all of the eigenvalues of a matrix.

We saw that \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of a matrix \(A\) if and only the equation \(\left(A - \lambda I\right)=0\) has non-zero solutions. But recall that this equation only has non-zero solutions if and only if the the matrix \(A - \lambda I\) is invertible, which is the case if and only if its determinant is zero. Therefore, we have the following important theorem.

Theorem

Given a square matrix \(A\), a real number \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) if an only if

The equation \(f(\lambda)=\mathrm{det}\left(A - \lambda I\right)\) is called the characteristic polynomial of \(A\).

20.4. Calculating Eigenvalues#

We now have the necessary tool to calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of any square matrix \(A\).

Calculating Eigenvalues

Let \(A\) be a square matrix. To determine the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(A\),

Calculate the characteristic polynomial \(f(\lambda)=\mathrm{det}\left(A - \lambda I\right)\) using the rules for calculating determinants.

Solve the degree-\(n\) polynomial equation \(f(\lambda) = 0\). Each solution \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\).

Determine the corresponding eigenspaces using row-reduction on the matrix \(A-\lambda I\) for each eigenvalue \(\lambda\).

For \((2\times 2)\) matrices, we can always following procedure directly to find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Example: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors of a \((2\times 2)\) Matrix

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix

Answer

1. Calculate the characteristic polynomial:

2. Solve \(f(\lambda)=0\):

Therefore the eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1 = 3+2\sqrt{2}\) and \(\lambda_2 = 3-2\sqrt{2}\).

3. Determine the eigenvectors by row-reduction:

Reduces to:

and the general solution to \(\left(A - \lambda_1I\right)v=0\) is

Therefore \(v_1 = \begin{pmatrix}1+\sqrt{2} \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\) is an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\lambda_1 = 3 + 2\sqrt{2}\).

Similarly, we can calculate that \(v_2 = \begin{pmatrix}1-\sqrt{2} \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\) is an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\lambda_2 = 3 - 2\sqrt{2}\).

For larger matrices, calculating eigenvalues by hand can be challenging due to the fact that we have calculate determinants (hard!) and find the roots of polynomials (hard!). In the example below, calculating the determinant is made easier due to the presence of zeros in the off-diagonal entries of the matrix. A little bit of guess-work allows us to find one root of the characterstic polynomial, then we use polynomial division to find the other roots.

In practice however, we need to resort to a numerical methods - implemented on a computer - to find eigenvalues and eigenvectors of large matrices.

Example: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors of a \((3\times 3)\) Matrix

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix

Answer

1. Calculate the characteristic polynomial:

2. Solve \(f(\lambda)=0\):

In general, factorising cubic polynomials is hard. However, in this case (by trial and error) we can determine that \(f(2)=0\) and therefore \(\lambda-2\) is a root of the characteristic polynomial. To find the other roots, we can use polynomial long division:

Therefore,

so the only eigenvalues are \(\lambda=2, -1\).

3. The eigenspace corresponding to \(\lambda=2\) is the null space of \(A-2I\).

which reduces to

from which we can calculate the special solution

and so the eigenspace corresponding to eigenvector \(\lambda=2\) is

The eigenspace corresponding to \(\lambda=-1\) is the null space of \(A+I\).

which reduces to

from which we can calculate the special solution

and so the eigenspace corresponding to eigenvector \(\lambda=-1\) is

Exercise 20.3

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrix

20.5. Solutions to Exercises#

Solution to Exercise 20.1

Therefore \(v_1\) is an eigenvector of \(A\) with eigenvalue \(\lambda_1 = 2\)

is not a scalar multiple of \(v_2\) therefore \(v_2\) is not an eigenvector of \(A\).

Solution to Exercise 20.2

\(\lambda = -2\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) if the equation \(\left(A + 2I\right)v = 0\) has non-zero solutions.

The reduced row echelon form of this matrix is

and the general solution to \(\left(A + 2I\right)v=0\) is

Therefore \(\lambda = -2\) is an eigenvalue with corresponding eigenvector \(v = \begin{pmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{pmatrix}\).

Solution to Exercise 20.3

1. Calculate the characteristic polynomial.

2. Solve \(f(\lambda) = 0\):

Eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1=2, \lambda_2=\sqrt{3}, \lambda_3=-\sqrt{3}\).

3. The eigenspace corresponding to \(\lambda_1=2\) is the null space of

Reducing to reduced row echelon form:

so the corresponding eigenvector is

The eigenspace corresponding to \(\lambda_2=\sqrt{3}\) is the null space of

Reducing to reduced row echelon form:

so the corresponding eigenvector is

The eigenspace corresponding to \(\lambda_2=-\sqrt{3}\) is the null space of

Reducing to reduced row echelon form:

so the corresponding eigenvector is