Matrix Diagonalisation

Contents

21. Matrix Diagonalisation#

21.1. Motivation#

Recall that a diagonal matrix is a square matrix with zeros everywhere except the main diagonal. Multiplying a vector by a diagonal matrix \(D\) is easy. Just multiply each entry of the vector by the the element in the corresponding position of the diagonal matrix:

In fact, for diagonal matrices we immediately have the eigenvalues and eigenvectors! The eigenvalues are the diagonal entries \(d_i\) and the eigenvectors are the standard coordinate vectors \(e_i\):

Multiplying by a diagonal matrix is easy because any vector is a linear sum of coordinate vectors. The diagonal entries of \(D\) act separately on each of the components of the vector \(x\).

What about general (non-diagonal) square matrices? If \(x\) is an eigenvector of a square matrix \(A\) and \(\lambda\) its eigenvalue, then we have

If \(x\) is an eigenvector, \(A\) behaves like a diagonal matrix. Instead of writing \(x\) as a sum of coordinate vectors \(e_i\), we write it as a sum of eigenvectors \(v_i\):

Then

We just need to find the values \(a_i\). It turns out that these are just the inverse of the matrix of eigenvectors, as we will see in the next section.

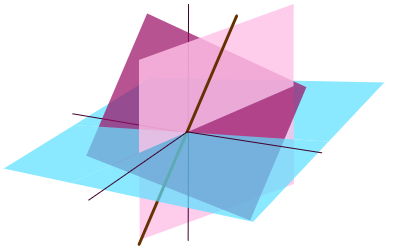

21.2. Diagonalisation \(A = X\Lambda X^{-1}\)#

Matrix Diagonalisation

Let \(A\) be an \((n \times n)\) matrix with \(n\) eigenvectors \(v_i\) and corresponding eigenvalues \(\lambda_i\). Let

be the matrix of eigenvectors and

the diagonal matrix of eigenvalues. If \(X\) is invertible, then

and

Note that we use capital lambda \(\Lambda\) to represent the matrix of eigenvalues.

To see why the above result is true, note \(X^{-1}AX=\Lambda\) and \(A = X\Lambda X^{-1}\) are both exactly equivalent to:

Then the left hand side \(AX\) is \(A\) times the eigenvectors:

because \(Av_i= \lambda_iv_i\).

Whereas right hand side \(X\Lambda\) is the eigenvectors times the eigenvalues:

Thus we see that \(AX=X\Lambda\).

Example

Diagonalise the \((2 \times 2)\) matrix

Solution

This matrix represents a reflection in the line \(y=-x\) so we can immediately write down two eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors:

Therefore we can write the matrix of eigenvectors \(X\) and matrix of eigenvalues \(\Lambda\):

To complete the diagonalisation we need to calculate \(X^{-1}\):

Then

The matrix of eigenvectors \(X^{-1}\) is also called the change of basis matrix. Multiplying a vector \(x\) by \(X^{-1}\) transforms it from standard coordinates \(e_1, \ldots, e_n\) to eigenvector coordinates \(v_1, \ldots, v_n\).

Suppose \(x\) is written as a sum of eigenvectors with coefficients \(a_i\):

then left-multiplying by \(X^{-1}\) gives the vector of coefficients \(a_i\):

Note

Diagonalisation is not unique

1. If we write the eigenvalues and eigenvectors in a different order, we get a different matrix \(X\). Swapping \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) we get another way to write (21.1):

However it is important that the order of the eigenvalues is the same as the order of the eigenvectors. If you swap the eigenvectors, you must remember to also swap the eigenvalues!

2. Any eigenvector can be multiplied by a constant. For example replacing \(v_1\) by \(2v_1\) in (21.1):

3. The eigenvalues are unique, although different diagonalisations may result in a different order.

Exercise 21.1

Diagonalise the matrix

21.3. About Diagonalisation#

Not all matrices can be diagonalised. To diagonalise a matrix, the matrix of eigenvectors \(X\) must be invertible. In this section we will investigate conditions under which this is the case.

Recall that if \(v\) is an eigenvector then so is any multiple \(av\). Suppose a \((2 \times 2)\) matrix has eigenvector \(v\). Then the vector \(2v\) is also an eigenvector, but the eigenvector matrix

is not invertible since the second column is a multiple of the first (and therefore its determinant is zero).

We can extend this idea to \((3 \times 3)\) matrices. Suppose we have two independent eigenvectors \(v_2\) and \(v_2\) and a third eigenvector \(v_3\) such that \(v_3 = av_1 + bv_2\) for some scalars \(a\) and \(b\). Then the matrix of eigenvectors

is not invertible. To extend this idea to the general case, we need to introduce the important concept of linear independence.

21.4. Linear Independence#

A set of vectors is linearly dependent if one vector can be written as a linear sum of the other vectors.

Definition

Let \(v_1, \ldots, v_n \in \mathbb{R}^m\) be a set of vectors.

The vectors are linearly independent if the equation

has only the trivial solution

Otherwise, we say the vectors are linearly dependent.

Exercise 21.2

Show that a set of vectors is linearly dependent if (and only if) one of the vectors is a linear sum of the others.

If we have \(n\) linearly dependent vectors \(v_i \in \mathbb{R}^n\) then it is easy to show that the matrix

is not invertible. Therefore we can extend the invertible matrix theorem with two more equivalent conditions for invertibility:

Invertible Matrix Theorem (II)

Let \(A\) be an \((n \times n)\) matrix. Then the following statements are equivalent:

\(A\) is invertible.

\(\mathrm{det}(A) \neq 0\).

\(A\) has \(n\) pivots.

The null space of \(A\) is 0.

\(Ax=b\) has a unique solution for every \(b \in \mathbb{R}^n\).

The columns of \(A\) are linearly independent.

The rows of \(A\) are linearly independent.

21.5. More Eigenvalues#

Theorem

Eigenvectors \(v_1, \ldots, v_n\) corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are linearly independent.

An \((n \times n)\) matrix with \(n\) distinct eigenvalues is diagonalisable.

To prove this, suppose that \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are linearly dependent eigenvectors of the matrix \(A\) with distinct eigenvalues \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\).

for some \(a\neq 0\).

Multiply by A:

then divide by \(\lambda_2\) (since they are distinct we can assume that at least one of the eigenvalues is nonzero).

Comparing (21.2) and (21.3) we see that \(\lambda_1/\lambda_2=1\) and so

\(\lambda_1 = \lambda_2\).

We have shown that two linearly dependent eigenvectors must have identical eigenvalues. We will not show it here, but it is not difficult to extend this to the general case: eigenvectors from distinct eigenvalues are linearly independent.

We can conclude that if an \((n \times n)\) matrix has \(n\) distinct eigenvalues then it has \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors. By the invertible matrix theorem we can therefore can conclude that its matrix of eigenvectors \(X\) is invertible, and the matrix is invertible.

Example

Determine the characteristic equation of each of the following matrices and identify which are diagonalisable:

Solution

\(A\) has characteristic polynomial \(\lambda^2 - 1 = (\lambda-1)(\lambda+1)\). It has two distinct eigenvalues \(\lambda_1=1\),\(\lambda_2=-1\) and therefore two independent eigenvectors. It is diagonalisable and we already calculated \(A = X\Lambda X^{-1}\) (21.1).

\(B\) has characteristic polynomial \(\lambda^2-2\lambda = \lambda(\lambda - 2)\). It has two distinct eigenvalues \(\lambda_1=0\),\(\lambda_2=2\) and therefore has two independent eigenvectors and is diagonalisable.

\(C\) has characteristic polynomial \(\lambda^2-2\lambda+1 = (\lambda-1)^2\). It has a single eigenvalue \(\lambda_1=1\). To determine if \(C\) is diagonalisable, we need to check if there are two independent eigenvectors in the eigenspace of \(\lambda_1\).

\(C\) has only one linearly independent eigenvector and therefore it is not diagonalisable.

Exercise 21.3

Diagonalise the matrix \(B\) in the example above.

Find a diagonalisable matrix with only one distinct eigenvalue.

Attention

Diagonalisability is not related to invertibility. Non-invertible matrices can be diagonalisable, as in \(B\) above. Likewise, non-diagonalisable matrices can be invertable as in \(C\) above.

21.6. Algebraic and Geometric Multiplicity#

The eigenvalues of a \((n \times n)\) square matrix are the roots of its characteristic polynomial \(f(\lambda)\). We have already seen that if there are \(n\) distinct roots then there are \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors and the matrix is diagonalisable. For example a \((3 \times 3)\) matrix with the following characteristic polynomial is diagonalisable.

If there are fewer then \(n\) distinct roots then at least one of the roots must be repeated. For example, the characteristic polynomial

results in two distinct eigenvalues \(\lambda_1=2\) and \(\lambda_2=1\). \(\lambda_2\) is a repeated root with multiplicity \(2\) since the factor \((\lambda-1)\) divides the polynomial twice. To determine whether the matrix is diagonalisable, we need to determine how many independent eigenvectors there are in the eigenspace of each of the eigenvectors.

Theorem

Let \(A\) be a square matrix and \(\lambda\) an eigenvalue of \(A\). Then,

geometric multiplicity of \(\lambda\) \(\leq\) algebraic multiplicity of \(\lambda\)

where the algebraic multiplicity of \(\lambda\) is its multiplicity as a root of the characteristic polynomial of \(A\) and the geometric multiplicity of \(\lambda\) is the number of independent eigenvectors in the eigenspace of \(\lambda\).

This means that for (21.4) there could be one or two independent eigenvectors in the eigenspace of \(\lambda_2\). If there are two, then the matrix is diagonalisable; if only one then it is not diagonalisable. To check, we have to calculate the null space of \(A-\lambda_2I\).

21.7. Matrix Powers \(A^k\)#

The eigenvector matrix \(X\) produces \(A=X\Lambda X^{-1}\). This factorisation is useful for computing powers because \(X^{-1}\) multiplies with \(X\) to get \(I\):

and so on. Because \(\Lambda\) is a diagonal matrix, its powers \(\Lambda^k\) are easy to calculate.

Theorem

Let \(A\) be a diagonalisable square matrix with \(A = X\Lambda X^{-1}\) and \(k\in \mathbb{N}\). Then

21.8. Complex Eigenvalues#

We have seen that from a square matrix \(A\) we can calculate the characteristic polynomial \(f(\lambda)\). For an \((n \times n)\) matrix the polynomial is degree \(n\):

where \(a_i\) are real numbers.

By the fundamental theorem of algebra, \(f(\lambda)\) can be factorised into \(n\) factors \(\lambda - \lambda_i\) (some of which may be repeated):

The roots \(\lambda_i\) are the eigenvalues of the matrix.

In this section we consider the case where some of the roots are not real numbers.

21.8.1. Rotations in 2D#

Let \(A\) be the matrix of an anticlockwise rotation \(\pi/2\) around the origin:

The characteristic polynomials is \(\det(A-\lambda I)\) which equals

The polynomial \(\lambda^2+1\) does not have real roots. Its roots are \(\pm i\) where \(i\) is the imaginary number \(\sqrt{-1}\):

resulting in two complex eigenvalues \(\lambda_1 = i\) and \(\lambda_2= -i\).

We also find that the eigenvectors contain the imaginary number \(i\):

and hence the eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\lambda_1 = i\) is

Likewise the eigenspace corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\lambda_2 = -i\) is

Example

Find the eigenvalues of an anticlockwise rotation by an angle \(\theta\).

Solution

The matrix

represents an anticlockwise rotation by an angle \(\theta\). The characteristic polynomial \(f(\lambda)\) is given by

Setting this to zero and solving for \(\lambda\) gives eigenvalues

Exercise 21.4

Find the complex eigenvectors corresponding to the two complex eigenvalues of

21.9. Trace and Determinant#

Calculating eigenvalues is (in general) a difficult problem. However, in some cases we can use some ‘tricks’ to help find them.

Definition

The trace of a matrix is the sum of the diagonal entries. Given a matrix \(A\) with entries \(a_{ij}\):

Theorem

Let \(A\) be an \((n \times n)\) matrix with eigenvalues \(\lambda_1, \ldots, \lambda_n\). Then

and

The sum of the eigenvalues is the sum of the diagonal entries of \(A\). The product of the eigenvalues is the determinant of \(A\).

Example

Calculate the determinant of the matrix

Solution

This matrix is clearly not invertible, and so has zero determinant and at least one zero eigenvalue.

In fact there are two independent eigenvectors in the zero eigenspace (check this!). This means that we have \(\lambda_1=\lambda_2=0\). To find the third eigenvalue, use the identity

to determine that \(\lambda_3=3\).

Exercise 21.5

Show that the eigenvalues of a triangular matrix are its diagonal entries.

21.10. Solutions to Exercises#

Solution to Exercise 21.1

First find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(A\). The characteristic polynomial is given by:

therefore the two eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1 = -1\) and \(\lambda_2=2\).

To find the corresponding eigenvectors, calculate the nullspace of \(A - \lambda I\) for each eigenvalue. For \(\lambda_1\):

Therefore \(v_1 = \begin{pmatrix}-1\\1\end{pmatrix}\) is an eigenvector corresponding to eigenvalue \(\lambda_1=-1\).

For \(\lambda_2\):

Therefore \(v_2 = \begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}\) is an eigenvector corresponding to eigenvalue \(\lambda_2=2\).

The matrix of eigenvectors is

and its inverse

The matrix of eigenvalues is

and so

Solution to Exercise 21.3

1. Eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1 = 0\), \(\lambda_2=1\).

\(B-\lambda_1I = \begin{pmatrix}1&1\\1&1\end{pmatrix}\underrightarrow{\mathrm{~RREF~}}\begin{pmatrix}1&1\\0&0\end{pmatrix}\)

Therefore \(v_1 = \begin{pmatrix}1\\-1\end{pmatrix}\).

\(B-\lambda_2I = \begin{pmatrix}-1&1\\1&-1\end{pmatrix}\underrightarrow{\mathrm{~RREF~}}\begin{pmatrix}-1&1\\0&0\end{pmatrix}\)

Therefore \(v_2 = \begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}\).

and

The eigenvalue matrix \(\Lambda\) has a zero on the diagonal because one of the eigenvalues is zero.

2. A matrix of the form

has characteristic polynomial

and therefore a single repeated eigenvalue \(\lambda=a\).

But it is diagonalisable (it is diagonalised by the identity matrix). In fact, every vector \(v \in \mathbb{R}^2\) is an eigenvector of the matrix.