Linear Independence and Bases

Contents

13. Linear Independence and Bases#

13.1. Linear Dependence#

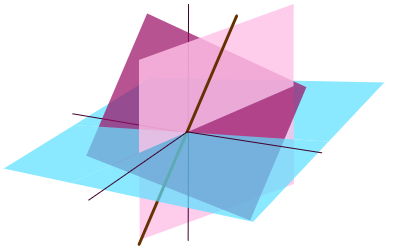

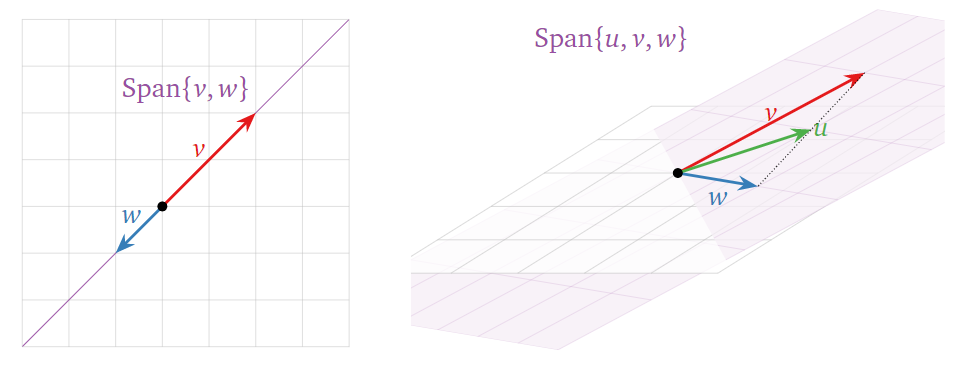

Sometimes the span of a set of vectors is ‘smaller’ than you expect from the number of vectors, as in the picture below. This means that (at least) one of the vectors is redundant: it can be removed without affecting the span.

In each case, one vector is in the span of the others — so it doesn’t make the span bigger.

A set of \(k\) vectors \(\{v_1, \ldots, v_k\}\) is linearly dependent if one of the vectors can be written as a linear combination of the others.

Example

Linearly dependent set of vectors

This set of three vectors are linearly dependent since the third vector can be written as a linear combination of the first two.

Linearly independent set of vectors

This set of three vectors are linearly independent since none of the vectors is a linear combination of the other two.

13.2. Linear Independence#

The above formulation of linear dependence is not very easy to check. Fortunately, there is a defintion of the opposite — linear independence — which is usually taken as the standard definition.

A set of vectors \(\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\}\) is linearly independent if and only if the equation

has only the trivial solution, where

Otherwise, the set \(\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\}\) is linearly dependent.

To check whether a set of vectors is linearly independent we simply form the matrix \(A\) whose columns are the vectors \(v_1, \ldots, v_n\) then solve \(Ax = 0\). If there are any solutions except for \(Ax = 0\) then the vectors are linearly independent. The vector \(x = 0\) is always a solution of \(Ax = 0\) which is why we exclude the ‘trivial solution’ \(x = 0\)…

Example

Is the following set of vectors linearly independent?

Solution

This is equivalent to the homogeneous vector equation

Solve this by forming by row reducing the matrix formed from the column vectors:

We have one free variable \(x_3\) and the solution is:

Which is equivavlent to

for any \(t\in\mathbb{R}\).

We conclude that there are non-trivial solutions to \(Ax = 0\). The three vectors are linearly dependent and equation of linear dependence is

13.3. Bases#

Recall that the span of a set of vectors is all linear combination of the vectors. If a set of vectors is linearly dependent, then we can remove one or more vectors from it without changing the span. By removing these vectors until the remaining vectors are linearly independent, we arrive at a basis.

Given a set of vectors \(\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\}\), a basis for \(\mathrm{Span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\}\) is a linearly independent set of vectors \(\{w_1,\ldots,w_k\}\) such that \(\mathrm{Span}\{w_1,\ldots,w_k\}=\mathrm{Span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\}\).

It’s easiest to understand this definition by following a recipe for calculating a basis.

How to calculate a basis

Let \(\left\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\right\}\) be a set of vectors.

Then the pivot columns in the matrix

form a basis for \(\left\{v_1,\ldots,v_n\right\}\).

Example

Find a basis for

Solution

Form a matrix from the vectors and reduce to echelon form. The vectors are the same as the ones in the previous example, so we already know its RREF:

This tells us that the third vector (corresponding to a free variable in the matrix \(A\)) can be written as a linear combination of the other two (corresponding to pivots). So we discard the third column; the remaining columns form a basis:

\(\left\{\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\\1\end{pmatrix},\begin{pmatrix}1\\-1\\2\end{pmatrix}\right\}\) is a basis.