Linear Transformations

Contents

15. Linear Transformations#

In this section we learn to understand matrices geometrically as functions, or transformations. We briefly discuss transformations in general, then specialize to matrix transformations, which are transformations that come from matrices.

15.1. Linear Transformations#

A function is a rule that takes inputs and transforms them to outputs. For example, a function \(f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\),

is a function that takes a real number \(x\) as input and outputs another real number, the square of the input. On the other hand, the function \(g:\mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\),

is a function which maps 2-dimensional vectors \((x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2\) to real numbers.

Functions can also be defined geometrically. For example, the following are valid function definitions:

\(R_\theta:\mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^2\) corresponding to a \(\theta\) anticlockwise rotation around the origin.

\(U:\mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^2\) corresponding to a translation by the vector \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\-1\end{pmatrix}\).

Definition

Suppose \(f:\mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) is a function such that

and

for all \(u, v \in\mathbb{R}^n\) and \(a\in\mathbb{R}\).

Then \(f\) is a linear transformation.

Attention

In mathematics, the words function, map and transformation can be used interchangeably. So ‘linear function’, ‘linear map’ and ‘linear transformation’ all have the same meaning.

In practice, we often prefer the word ‘transformation’ when we want to emphasise the geometrical nature of a function.

You can think of this definition as the transformation of any linear combination of vectors is the same as the linear combination of the transformed vectors.

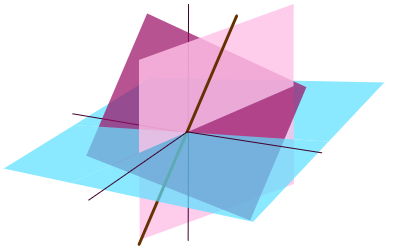

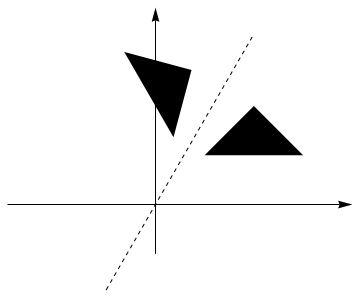

Rotation is an example of a linear transformation:

We can add vectors \(u\) and \(v\) and then rotate, or we can rotate \(u\) and \(v\) and then add, as illustrated in Fig. 15.1.

We can scale \(u\) and then rotate, or we can rotate \(u\) and then scale.

Fig. 15.1 The parallelogram rule for vector addition shows that \(R_\theta(u + v) = R_\theta(u) + R_\theta(v)\).#

Properties of Linear transformations

If \(T:\mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) is a linear transformation, then

and for any vectors \(v_1,\ldots,v_k \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and scalars \(a_1,\ldots a_k \in \mathbb{R}\)

The first property \(T(0)=0\) follows from the second part of the definition of linearity. Note that here \(0\) represents a vector and we geometrically we can think of this as saying that a linear transformation takes the origin to the origin.

Example

1. A non-linear transformation

The transformation \(T:\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(T(x) = x + 1\) is not a linear transformation.

We can easily prove this by showing that \(T\) fails to fix the origin:

Therefore \(T\) is not a linear transformation, even though the graph of \(T(x)\) is a straight line.

2. A linear transformation

Suppose \(U:\mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\) be defined by \(U(x) = 2x\).

\(U\) is a dilation which doubles the size of every vector. We show that this is a linear transformation by checking the definition. Let \(u, v \in \mathbb{R}^2\) and \(a \in \mathbb{R}\). Then

and

Exercise 15.1

Which of the following functions are linear transformations?

1. \(T:\mathbb{R}^2\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^2\),

2. \(f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\),

3. \(U:\mathbb{R}^3\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^2\),

15.2. Matrix Transformations#

Now let \(A\) be an \((m \times n)\) matrix. Then \(A\) defines a function

where

In other words, \(A\) defines a function which takes a vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and transforms it to a vector \(Ax \in \mathbb{R}^m\). In fact, it turns out that the function defined by multiplication by a matrix is a linear transformation.

Theorem

If \(A\) is an \((m \times n)\) matrix \(A\) then the function

defined by

is a linear transformation which takes the vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) to the vector \(Ax \in \mathbb{R}^m\).

The proof of this follows directly from the definitions of matrix arithmetic:

There is essentially nothing new here, beyond the notation and a slightly different way of thinking about matrix multiplication. In the next section we will see how thinking of a matrix as a transformation allows us to picture its effect geometrically.

15.3. Geometrical Interpretation of Matrices#

Consider the matrix

which defines the linear transformation \(T:\mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\) defined by \(T(x) = Ax\).

Given a vector \(x=\begin{pmatrix}x_1\\x_2\end{pmatrix}\) we can consider the effect of the transformation \(T\):

Multiplication by \(A\) negates the \(x_1\) co-ordinate and leaves the \(x_2\) co-ordinate unchanged i.e. it reflects over the \(x_2\) axis.

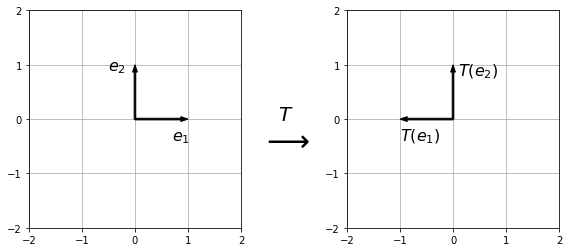

We can illustrate this by picturing the effect of the transformation on the unit co-ordinate vectors \(e_1 = \begin{pmatrix}1\\0\end{pmatrix}\) and \(e_2=\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\end{pmatrix}\):

Furthermore, once we know the transformed unit vectors, we can use the linearity of the transformation to determine how any vector is transformed. Given a vector \(x = \begin{pmatrix}x_1\\x_2\end{pmatrix}\), we can write \(x\) as a sum of unit co-ordinate vectors:

and use the linearity property to calculate the result

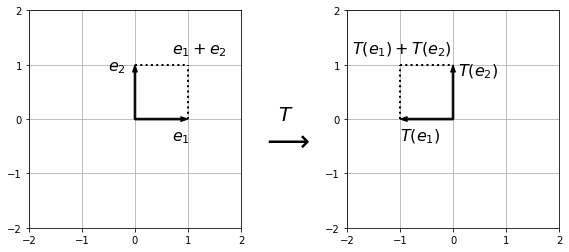

For example, the vector \(e_1 + e_2\) is transformed to \(T(e_1) + T(e_2)\) so we can use this to draw the image of the unit square which has vertices \(0\), \(e_1\), \(e_2\) and \(e_1 + e_2\):

Example

Determine the geometrical effect of the transformation given by the matrix

Solution

\(A\) represent a rotation anticlockwise by \(\pi/4\).

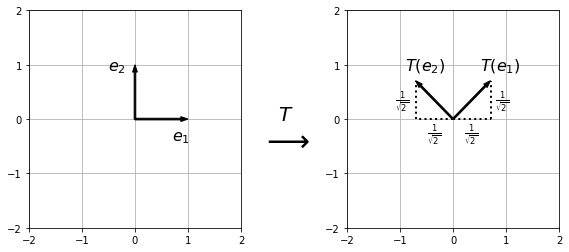

Exercise 15.2

Describe the geometrical effect of the following matrices:

1. \(A = \begin{pmatrix}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\\\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\end{pmatrix}\)

2. \(B = \begin{pmatrix}k & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\)

3. \(C = \begin{pmatrix}1 & k\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\)

15.4. The Matrix of a Linear Transformation#

In this section will learn that all linear transformations are matrix transformations - in other words, any function \(T\) which satisfies the linearity properties can be written as a matrix \(T(x) = Ax\). Before doing so, we need the following important notation.

Definition

The standard coordinate vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) are the \(n\) vectors

The standard coordinate vectors are useful because of the following property:

Multiplying a matrix by the standard co-ordinate vector \(e_i\) selects the \(i\)th column of the matrix.

Suppose that an \((m \times n)\) matrix \(A\) is composed of the \(n\) column vectors \(v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_n\). Then,

For example,

Theorem

Let \(T:\mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) be a linear transformation. Then the \((m \times n)\) matrix

is the matrix corresponding to the transformation \(T\) and \(T(x)=Ax\).

Using this theorem, we can write down the matrix of any linear transformation.

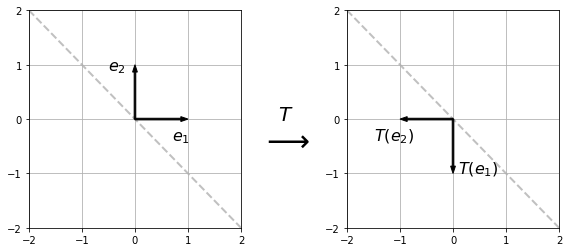

Example

Determine the matrix of the linear transformation \(T:\mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\) corresponding to reflection across the line \(x_2 = -x_1\).

Solution

First, determine the transformation of the unit coordinate vectors.

Therefore the matrix,

is the matrix of the transformation \(T\).

Exercise 15.3

1. Find the transformation of the basis vectors under reflection in the line \(y=kx, k\in\mathbb{R}\), giving your answer in terms of the angle between the line and the \(x\)-axis. Hence, find the image of the triangle with vertices \((1,3)\), \((3,1)\), \((2,2)\) under reflection in the line \(y=\sqrt{3}x\).

2. Sketch the image of the unit square with vertices \((0,0)\), \((0,1)\), \((1,0)\), \((1,1)\) under the linear transform \(\left(\begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\3 & 1 \\\end{array}\right)\). Try to describe this transformation in words.

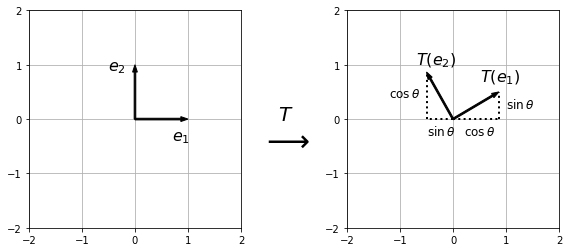

15.5. Rotation matrices in 2D#

Suppose the linear transformation \(T:\mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\) corresponds to an anticlockwise rotation by an angle \(\theta\) around the origin. Then we can use trigonometry to determine the destination of the coordinate vectors under \(T\):

Rotation Matrix

The matrix corresponding to an anticlockwise rotation by \(\theta\) degrees around the origin is given by:

15.6. solutions#

Solution to Exercise 15.1

1. and 2. Non-linear.

3. Linear.

Solution to Exercise 15.2

1. \(A = \begin{pmatrix}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\\\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}&\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\end{pmatrix}\)

\(A\) projects vectors onto the line \(y=x\).

2. \(B = \begin{pmatrix}k & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\)

\(B\) stretches vectors parallel to the \(x\)-axis by a scale factor \(k\).

3. \(C = \begin{pmatrix}1 & k\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\)

\(C\) represents a vertical shear by a factor \(k\).

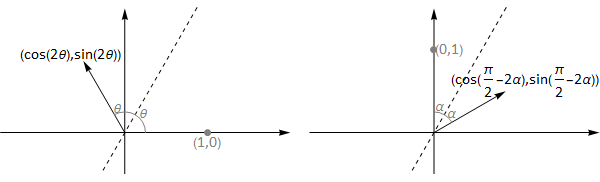

Solution to Exercise 15.3

1. The transformation of the basis vectors, shown in the graphic below is:

Fig. 15.2 reflection of basis vectors in the line \(y=\mathrm{tan}(\theta)x\).#

and so the transformation matrix is \(T=\left(\begin{array}{cc}\cos 2\theta & \sin 2\theta \\ \sin 2\theta & -\cos 2 \theta \end{array}\right)\)

For the line \(y=\sqrt{3}x\) we have \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{3}\), so \(T=\left(\begin{array}{cc}\cos(2\frac{\pi}{3})&\sin(2\frac{\pi}{3})\\\sin(2\frac{\pi}{3})&-\cos(2\frac{\pi}{3})\end{array}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\begin{array}{cc}-1 & \sqrt{3} \\\sqrt{3} & 1 \\\end{array}\right)\).

The transformation of the given points is

A plot of the reflection is shown below.

Fig. 15.3 reflected triangle.#

2.

The image below shows the unit square under the transform \(\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&0\\k&1\end{array}\right)\) as the constant \(k\) is adjusted between 0 and 3.

Fig. 15.4 vertical shear.#

Note that we can write this transform as \(\left(\begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\0 & 1 \\\end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{cc}0 & 0 \\k & 0 \\\end{array}\right)\).

The first term is just the identity matrix that maps points to themselves, and the second term transforms the y coordinate of each point by an amount proportional to the \(x\) coordinate, so points that are further from the \(y\)-axis are stretched more. This type of transform is known as a vertical shear.

We can achieve the same effect parallel to the horizontal axis by taking the transform (known as horizontal shear by taking the transform \(\left(\begin{array}{cc}1&k\\0&1\end{array}\right)\).