Techniques of Proof

Contents

14. Techniques of Proof¶

14.1. Proof by Contradiction¶

This is a form of proof that seeks to establish if the validity of a proposition by showing that by assuming the proposition is false leads to a direct contradiction. We can summarise the technique as:

The statement to proven \(P\) is assumed false, i.e. assume \(\lnot{P}\) is true.

\(\lnot P\) leads directly to assertions \(Q\) and \(R\), such that \(R = \lnot Q\).

Since \(Q\) and \(\lnot Q\) cannot both be simultaneously true, \(\lnot P\) is also untrue and hence \(P\) is true.

By way of an example, consider this classic proof from Euclid:

Statement: There are infinitely many prime numbers

Proof: The fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that every positive integer (other than 1) can be represented in exactly one way (apart from rearrangement) as a product of one or more primes. Assume there are \(n\) finitely many prime numbers \(p\), then consider the number \(N\) composed of the product of all of the prime numbers from the first \(p_1 = 2\) up to the largest \(p_n\):

Now consider the number \(N+1\)

Since \(N+1\) is another whole number, it should be divisible by one of the prime numbers \(p={p_1,p_2,\dots,p_n}\), but clearly it cannot be - hence contradiction. Therefore there cannot be a finite number of primes and so there are an infinite number of primes. QED

14.2. Proof by Counterexample¶

This is form of proof that disproves a proposition by giving an example which is a direct contradiction to the proposition. This technique is often used to disprove a universal (or \(\forall\) type) statement. We can summarise the technique as:

The statement \(P\) is shown to be satisfied by an example \(E_1\) and it is assumed

A further example \(E_2\) is shown not to satisfy \(P\) or leads directly to assertion \(\lnot P\) being true.

Since \(P\) and \(\lnot P\) cannot both be simultaneously true, \(P\) cannot be held to be always true (although can be shown to sometimes hold).

By way of an example, consider this classic proof:

Statement: \(\forall n \in \mathbb{R}\), if \(n^2\) is divisible by 4, then \(n\) is divisible by 4.

Proof: We can find examples where this proof holds for both divisibility, e.g. \(n=4\), \(n^2 = 16\) and non-divisibility e.g. \(n=5\), \(n^2=25\).

However a counter example to this statement would be given by \(n = 6\), \(n^2=36\), here the \(n^2\) statement passes the test but \(n\) statement in the proposition does not - hence the statement can be shown not be always true. QED

14.3. Proof by Induction¶

This is a form of proof where a proposition, which is shown to be true for an initial case and a more general case \(n\), which then allows a higher general case \(n+1\) to be shown to be true. This idea of a higher and higher steps on a proof ladder can be quite a powerful technique. We can summarise the technique as:

A proposition \(P_n\) is shown to be true for an initial or base case, i.e. we can prove that the statement holds for \(0, 1\).

Assuming that the proposition is true for \(P_n\), we can show that it is true for \(P_{n+1}\).

By way of an example, consider this classic proof:

Statement: Prove that

Proof: \(S_1 = 1(2)/2 = 1\) which is true, \(S_2 = 2(3)/2 = 3\) which is also true.

Assuming that \(S_n\) is true, we need to see if we can prove \(S_{n+1} = (n+1)(n+2)/2\):

QED

Another example would be to:

Statement: Prove that

is always a multiple of 10.

Proof: If we take \(P_n: \quad 6^n + 4^{2n+1} = 10k,\, \{k,\,n\}\in \mathbb{N}\), then examining:

\(P_1: \quad 6^1 + 4^3 = 64 + 6 = 70 = 7(10)\)

\(P_2:\quad 6^2 + 4^5 = 26 + 1024 = 1050 = 105(10)\)

Thus proven for the first couple of cases, now we assume that \(P_n\) is true and look to \(P_{n+1}\), can we argue if this is true:

and therefore we have shown that \(P_{n+1}\) is also true.

14.4. Proof by Contraposition¶

We can summarise this technique as:

Given a statement \(P\) which leads directly to assertion \(Q\), i.e.

First order logic tells us that the negation of statement \(Q\), i.e. \(\neg Q\) leads directly to the negation of assertion \(P\), i.e. \(\neg P\),

By way of an example, consider this classic proof:

Statement: Prove that for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), if the function \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) is EVEN, then \(x\) is ODD.

Thus here \(P\) is \(x^2 - 6x + 5 = 2k,\, x \in \mathbb{R},\, k \in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(Q\) is \(x = 2a+1,\, a \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Proof: \(\neg Q\) here is assume \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) is EVEN, and \(\neq P\) here is \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) being ODD.

Lets write \(x = 2a\) with some \(a \in \mathbb{Z}\), then we find that:

which we can see clearly is ODD. Thus \(\neg Q \Rightarrow \neq P\) and so \(P \Rightarrow Q\) - i.e. when \(x\) is EVEN, \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) is ODD and therefore when \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) is EVEN, \(x\) is ODD. QED

Another example would be:

Statement: Prove that if \(n^2\) is EVEN, then \(n\) is EVEN, for all \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Thus here \(P\) is \(n^2 = 2k,\, k \in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(Q\) is \(n = 2a,\, a \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Proof: \(\neg Q\) here is \(n\) is ODD, i.e. \(n = 2a + 1,\, n \in \mathbb{N}\), then:

which is clearly an EVEN number plus one, which is ODD - hence \(\neg Q \Rightarrow \neg P\) and so \(P \Rightarrow Q\), i.e. if \(n^2\) is EVEN, then \(n\) is EVEN.

14.5. Proof By Construction¶

We can summarise this technique as:

Given a statement \(P_1\), we construct \(P_2,\,P_3,\,\dots,\,P_n\) which leads to assertion \(Q\),

Statement: Prove that for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), if the function \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) is EVEN, then \(x\) is ODD.

Proof: For \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), lets write \(x^2 - 6x + 5 = 2a\) with some \(a \in \mathbb{N}\), so that \(x^2 - 6x + 5\) is EVEN, then we find that:

Since the RHS is clearly ODD by construction, this means the LHS is ODD. Given that ODD \(\times\) ODD = ODD, then given \(x\) and \(x-6\) differ by an EVEN numbers, \(x\) must be an ODD number. QED

Another example of this technique would be to:

Statement: Prove that for \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\), \(n^3 - n\) is always a multiple of 6.

Proof: Examining this function:

Since every second number has to be an even number, the worst case scenario is one of \(n-1,\, n,\, n+1\) is EVEN and in the best case scenario two of \(n-1,\, n,\, n+1\) is EVEN. Likewise is every third number has to be a multiple of 3, one of \(n-1,\, n,\, n+1\) has to be multiple of 3.

Hence \(f(n) = (n-1)(n)(n+1)\) carries both factors of 2 and 3, therefore \(f(n)\) is always divisible by 6 if \(n \mathbb{Z}\).

14.5.1. Number Theory Types of Construction¶

Sometimes instead of directly proving a proposition, we can construct facts about the proposition which the lead to the answer. This is often employed when we have to prove some facts about numbers, for example lets try to prove that:

We could argue that this can be proved by induction, with proposition

and given the starting cases:

which works and therefore to shown the proposition true, we need to work out \((a+1)^5\):

and we can then argue that \(\forall \,a \in \mathbb{Z},\, a(a^3+1)\) is an EVEN number - if \(a\) is ODD then \(a^3+1\) is EVEN and so \(a(a^3+1)\) is EVEN and likewise if \(a\) is EVEN, \(a(a^3+1)\) is EVEN, hence we have:

which is \(P_a\Bigg|_{a \rightarrow a+1}\) and hence proven.

However lets explore the numbers a little deeper here, lets start with what happens if we square the first 10 natural numbers:

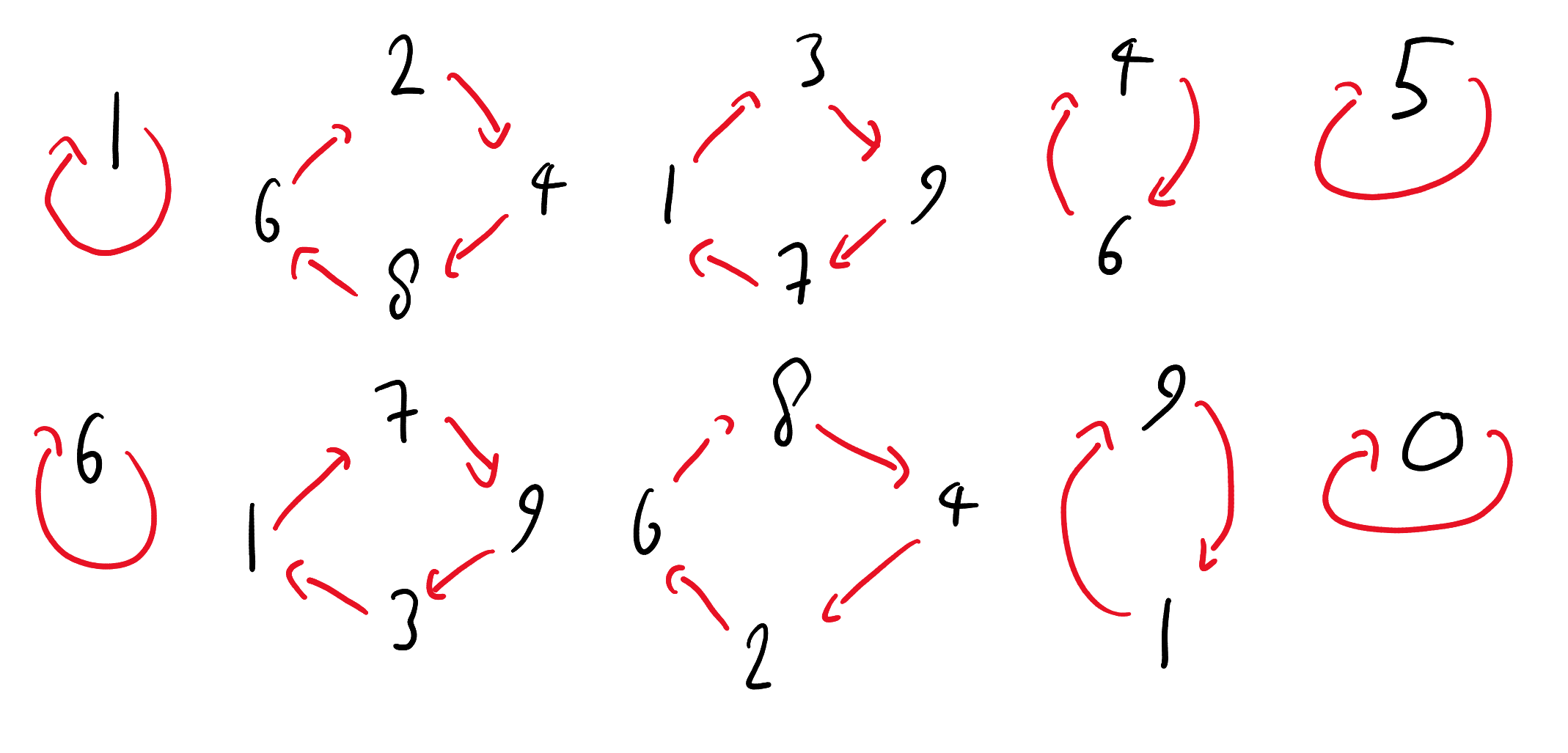

We notice that the last digit of the square numbers is always one of \(\{0,\, 1,\, 4,\, 5,\, 6,\, 9\}\), the digits \(\{2,\, 3,\, 7,\, 8\}\) never enter in to this. Likewise we could keep going to cube numbers and quartic powers etc, but lets just think about what happens when we take numbers to higher and higher powers - the last digit changes in a predictable way, as outlined in Fig. 14.1.

Fig. 14.1 The effect of higher and higher powers on the last digit of an integer.¶

We see that some digits under increasing integer powers return back to the same digit immediately (e.g. \(6 \rightarrow 6\)), others take another digit first (e.g. \(9 \rightarrow 1 \rightarrow 9\)) and some go through up to four other digits (e.g. \(2 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 6 \rightarrow 2\)), therefore for any digit, to guarantee the digit has returned we must raise the power to five, that’s why \(a^5\) will have a righthand digit equal to \(a\) plus another number that has a factor of ten, shifting it along to the higher digits.

Another example of using this technique would be to prove that:

is a multiple of 10.

Using the last digits powers in Fig. 14.1 for 4 and 6, we see that \(4^{2n+1}\) will always be a number ending in a 4 and the numebr \(6^n\) will always end in a 6, then the final digit of this number will always end in a 0 - this is therefore ALWAYS a multiple of 10 - hence proven!