Multidimensional Integrals

Contents

8. Multidimensional Integrals¶

Although we are used to find the area under a curve from the integral of a function \(f(x)\) over some limits \(x \in [a,\, b]\):

if we had some area described by a function \(f(x,\,y)\) we could try to find the area contained within this 2D shape. Likewise if we have some function \(f(x,\,y,\,z)\) describing some shape in 3D space, we could aim to find the total volume contained in this shape. We think of these as multidimensional integals as extending integral calculus to multivariables, akin to partial differentiation extending differential calculus to multivaribles.

8.1. Area Integrals¶

Formally we can think of some scalar field \(\phi({\bf r})\) which has as inputs \(\bf r\) which is some 2D position vector, which allows us to define:

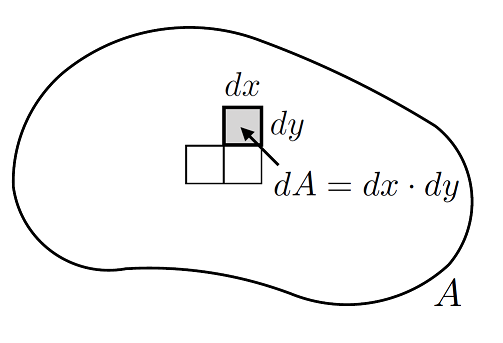

Conceptually we can think of \(\mathrm{d}A\) just like we do for the one variable case of integration, breaking up a shape into infintesimal blocks which we then sum up over the integral, as depicted in Fig. 8.1:

Fig. 8.1 Division of a 2-dimensional area A into infinitesimal area elements \(\mathrm{d}A\).¶

An area integral is a double integral, because we have to perform integrals over both the \(x\) and \(y\) variables. When integrating over one variable, the other is held constant - akin to how we do partial differentiation too.

Note that an important special case is \(\phi = 1\), where the area integral is equal to the total area, \(A = \int_A \,\mathrm{d}A\).

Otherwise what we are finding is an area weighed by the function \(\phi\) - if \(\phi(x,\,y)\) describes a function plotted on the \(z\) axis,

then the value of \(\phi\) in each infinitesimal box will be what is summedup by this area integral.

The order of the integration can however sometimes matter - this becomes important if the limits of each of the integals depends on one of the other variables (this can happen as when the integration is done, all the other variables are considered constant).

8.1.1. Area Integral Examples¶

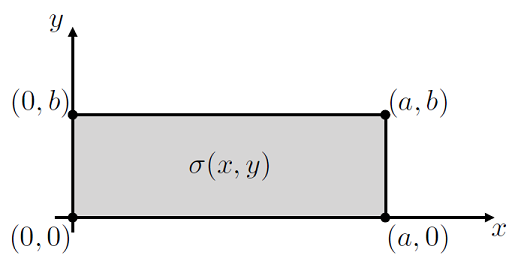

Lets think about a flat 2D sheet with some density \(\sigma(x,\,y)\) (mass per unit area), as depcited in Fig. 8.2,

Fig. 8.2 Rectangular plate with some density \(\sigma(x,\,y)\).¶

The total mass of the plate will be given by:

where we use the final notation for brevity and ease of expression - it does not mean not to include the \(\sigma\) term in the evaluation of the integrals.

If the rectangular plate has a uniform density, then \(\sigma\) is just a constant and we find:

If the rectangular plate has a uniform density, then we need to evaluate the integrals in turn, e.g. for \(\sigma(x,\, y) = y^2 + xy\), we can calculate the \(y\) integral first:

This is now reduced the 2D integral to a 1D integral, which we can evaluate:

If we reverse the order integration however, starting from the \(x\) integral, we find:

So we see in this case, the order of integration does not matter.

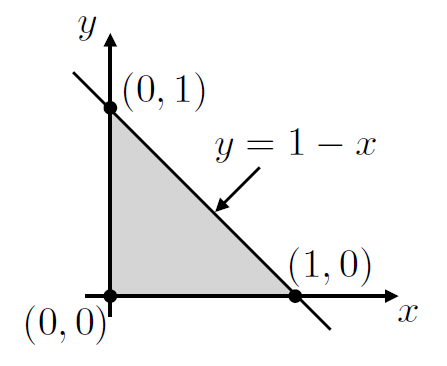

Lets look a more involved example, \(f(x,\,y) = x^2 + 2xy\) and we are interested in an area over a triangle, as depicted in Fig. 8.3:

Fig. 8.3 Triangular area with some function \(f(x,\,y) = x^2 + 2xy\) defined over it.¶

We see here that the limits of the two integrals cannot both be constant - upper limit of the \(y\) integral will change depending on the value of \(x\) (or vice-versa), hence \(x \in[0,\, 1]\) and \(y \in [0,\, 1-x]\) is one way to think about this area:

Now that there is some function of \(x\) in the limit, this says evaluate the \(y\) integral first and the \(x\) integral last:

We can also switch round the integration, but choosing to have \(y \in [0,\, 1],\, x \in [0,\, 1-y]\), which means that:

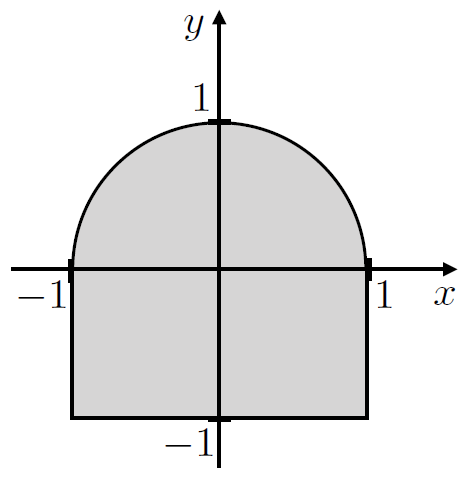

A final example looks at a trickier set of limits, lets try and calculate the integral \(I = \iint_A x^2y\,\mathrm{d}A\) for an area composed of a rectangle and a semi-circle, as depicted in Fig. 8.4:

Fig. 8.4 Area shown as a shaded region composed of a rectangle and a half circle.¶

If we pick \(x \in [-1,\,1]\), then the \(y\) limits should be between the lower limit \(y = -1\) and the upper limit at the semi-circle edge.

Given that \(x^2 + y^2 = 1\) is the equation of this line, then \(y = \sqrt{1-x^2}\), hence \(y \in [-1,\, \sqrt{1-x^2}]\), so the area is found by:

We could do this integral the other way round, but this is quite a bit tricker!

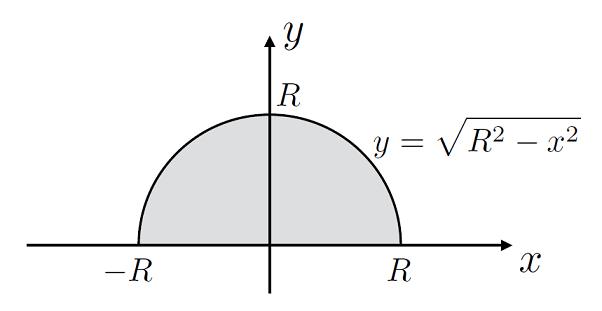

In fact the choice of coordinates we choose will not change the value of the integral either, lets look at doing these sorts of integral in polar coordinates, given \(y^2 + x^2 = R^2\) for \(y \geq 0\), as depicted in Fig. 8.5:

Fig. 8.5 Area shown as a shaded region composed of a half circle.¶

In Cartesian coordinates to find this area we would need to do:

which will then require an integral substitution to solve, quite a pain!

In polar coodinates this becomes:

which makes the result we expect!

8.2. Volume Integrals¶

The concept of an area integral can be extended to volume integrals. The integration region is now a volume having some shape. The integration egion is divided up into volume elements \(\mathrm{d}V\), and the function to be integrated \(\phi({\bf r})\) has a value in each element. Conceptually, the integral is the sum of all the contributions \(\phi({\bf r})\,\mathrm{d}V\) over all the elements, in the limit where the volume elements become infinitesimally small. In Cartesian coordinates, the volume element is simply \(\mathrm{d}V = \mathrm{d}x\,\mathrm{d}y\,\mathrm{d}z\), and the volume integral can be expressed as a triple integral over \(x, \,y,\, z\):

8.2.1. Volume Integral Examples¶

Lets think about volume integrals in Cartesian coordinates first, to calculate the volume integral of the function \(f(x,\, y,\, z) = \frac{1}{2} \left(x^2 + y^2 + z^2\right)\) over a cube whose 8 corners are at the points \((\pm 1,\, \pm 1,\, \pm 1)\):

If we wanted to find the volume of a sphere of radius \(R\), we could calculate this using cartesian coordinates, where \(x \in [-R,\, R]\) and then akin to the circle area in 2D \(y \in[-\sqrt{R^2 - x^2},\,-\sqrt{R^2 - x^2}]\) and finally to elevate this to a volume in 3D \(z \in[-\sqrt{R^2 - x^2 - y^2},\,-\sqrt{R^2 - x^2 - y^2}]\)

truely a nightmare to solve!

Instead lets switch to spherical polar coordinates, with \(r \in[0, \,R],\, \theta \in [0,\,\pi],\, \phi \in [0,\, 2\pi]\):

as expected.

Likewise we could find the volume of a cylinder with radius \(R\) and height \(H\) (recall this could be done through a solid of revolution type calculation, but here we aim to think about 3D axes), in Cartesian coordinates this would take the form of \(x \in [-R,\, R]\) then in 2D the circular cross section would be found through \(y \in [-\sqrt{R^2 - x^2},\,\sqrt{R^2 - x^2}]\) and then the height \(z \in [0,\, H]\), giving:

still not a great integral to compute, an integration variable chagne would be required.

In cylindrical polar coordinates however, \(r \in[0, R], \theta \in [0,\, 2\pi],\, z \in [0,\, H]\):

as expected.

A more complicated example would be to find the volume integral of \(f(x,\,y) = x^2y\) over a tetrahedral volume, bounded by the \(x-y\), \(y-z\) and \(x-z\) axes as well as \(x + y+ z = 1\), since all the bounding surfaces are symmetric in \(x,\, y,\, z\), there is no initial preference in integration order, however the integrand does not contain \(z\) so this is likely to be the easiest initial integral to compute, therefore:

with \(x = 0, \,y = 0,\, z = 0\) up to the plane \(x + y + z = 1\). Therefore in the \(z\) plane the limits are \(z \in[0,\, 1 - x - y]\) and likewise in the \(y\) plane the limits would be \(y \in [0,\, 1-x]\) (since \(z=0\) along this plane), hence along with \(x \in[0,\, 1]\):