Surface Integrals

Contents

9. Surface Integrals¶

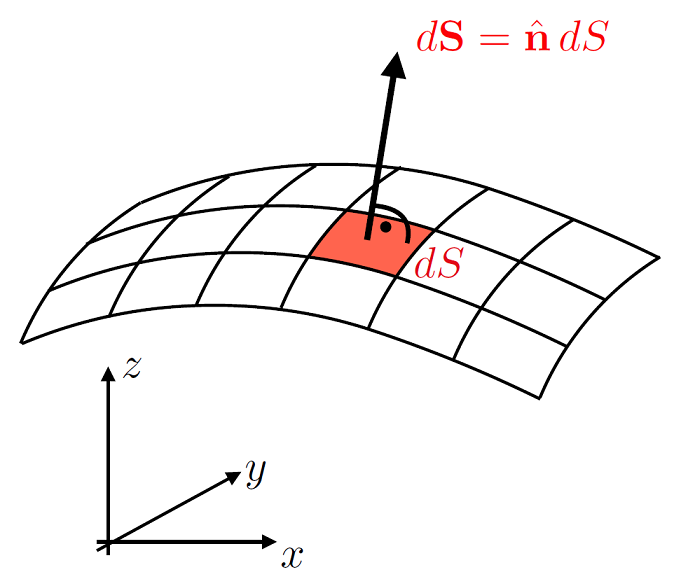

Now that we are happy with flat area and volume integrals, we can turn our attention to surfaces that are not flat, if we can break up the surface into area elements \(\mathrm{d}A\) and then integrate over the whole surface, we can use all the same techniques described so far to think about this. It is typical to define here an area vector \({\bf A}\) which points outwards from a surface and is in the normal direction to it:

although sometimes for a curves surface we will use the letter \(S\) for the surface normal. We can write the inifinitesimal area element as:

and this is depicted in Fig. 9.1.

Fig. 9.1 Some general surfece surface \(S\) with an infinitesimal surface element \(\mathrm{d}{\bf S}\).¶

For any scalar field \(f(r) = f(x,\, y,\, z)\) that is defined on all the points of the surface \(S\) we can define the Surface Integral as:

However this will only tell us the total amount of \(f\) on the surface \(S\), what is we instead had a vector field \({\bf G(r)}\) which crossed the surface \(S\)? Then in this case, the surface integral is given by:

We define this quantity as the flux of the vector field \(\bf G\) crossing the surface \(S\). Clearly as this has a scalar product, only the components parallel to \(\hat{\bf n}\) (perpendicular to \(S\)) will be summed over in the integral.

9.1. Calculating Surface Integrals¶

Similar to line integrals, we must parameterise the surface \(S\) in order for this integral to be possible, so we will pick

\(S = S({\bf r})\) with \({\bf r} = {\bf r}(s,\, t)\) with \(s \in[s_{min},\, s_{max}],\, t \in [t_{min},\, t_{max}]\).

This means that if we move from 2D parametrisation to a surface parameterisation, we can find infinitesimal changes

\(\mathrm{d}s,\, \mathrm{d}t\) that make up the \(\mathrm{d}S\) on the surface. We can then

define vectors \(\bf u,\, v\) which live on the surface:

and the final step is to find a cross product, this will produce the normal area vector, hence:

This means that in order to actually calculate the surface integrals we will need:

9.1.1. Example - Sphere¶

An example, finding the surface area of a sphere with radius \(R\), the most natural choice of \(s,\,t\) here would be angles \(\theta,\, \phi\):

hence we can calculate \(\mathrm{d}{\bf S}\) here:

We can then recall that the radial vector for spherical polar coordinates has the form:

and therefore :

Another way to see this is that \(\frac{\partial {\bf r}}{\partial \theta} \propto \hat{\theta}\) from the definition of the spherical coordinate system, likeise\(\frac{\partial {\bf r}}{\partial \phi}\ \propto \hat{\phi}\) therefore, we have \(\hat{\theta} \times \hat{\phi} = \hat{\bf r}\) from the definition of the cross products.

Thus the surface area integral takes the form:

9.1.2. Example of the form \(z = (x,\, y)\)¶

A different sort of example is where the coordinates \(x,\, y\) are defined as terms of \(z\), say \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = R^2\), which would describe the upper half of a sphere (recall the lower half would be

with the negative root). Here we have \(z = z(x,\,y)\), thus the parametirisation of thesurface is just in terms of \(x,\,y\) (a little like doing a line integral only in terms of \(x\)).

Thus the surface has a coordinate vector of the form:

meaning that the infinitemsimal surface vector element is given by:

Which means to solve this problem either we use this result with the scalar product of a vectof field \(\bf G\), \(I = \int {\bf G(r)}\cdot \mathrm{d}{\bf S}\). For a scalar field we have \(I = \int f\,\mathrm{d}S\), with:

Lets see this for \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 9\), thus \(z = \sqrt{9 - x^2 - y^2}\), lets consider the surface area over the range \(x \in [0,\,3],\, y \in [0,\, 3]\):

If we use a change of variable, \(x = \sqrt{9-y^2}\sin(\varphi) \Rightarrow \mathrm{d}x = \sqrt{9-y^2}\cos(\varphi)\,\mathrm{d}\varphi\) and therefore we have:

which corresponds to \(\frac{1}{8}\) of the full sphere’s surface area \(36\pi\), as expected.