Set Theory

Contents

11. Set Theory¶

Set theory is a branch of mathematics that studies collections of objects known as Sets. The language of set theory, which will start to study here, can be used to define almost all mathematical objects (if you are interested in what cannot be so easily defined, look up ideas such as Gödel’s incompleteness theorem and Russell’s Paradox).

11.1. Notation¶

There are lots of symbols in the notation used to describe mathematical objects, some of which we may have seen already. We can put together some elementary operations on sets:

Symbol |

Meaning |

Example |

|---|---|---|

\(\{ \}\) |

Defines a set |

e.g. \(A = \{1,\,2,\,3,\,4\}\), \( B = \{3,\,4,\,5\}\) |

\(A \cup B\) |

Union - in \(A\) OR \(B\) (OR both) |

\(A \cup B = \{1, \,2, \,3, \,4, \,5\}\) |

\(A \cap B\) |

Intersection - in \(A\) AND \(B\) |

\(A \cap B = \{3, \,4\}\) |

\(A \subseteq B\) |

Subset - every element of \(A\) is in \(B\) |

\(\{3,\,4,\,5\} \subseteq B\) |

\(A \subset B\) |

Proper Subset - every element of \(A\) is in \(B\), but \(B\) has more elements |

\(\{1,\, 2,\, 3\} \subset A\) |

\(A \not\subset B\) |

Not a Subset - \(A\) is not a subset of \(B\) |

\(\{1, \,5\} \not\subset A\) |

\(A \supseteq B\) |

Superset - every element of \(A\) is in \(B\) |

\( B \supseteq \{3,\,4,\,5\}\) |

\(A \supset B\) |

Proper Superset - every element of \(B\) is in \(A\), but \(A\) has more elements |

\(A \supset \{1, \,2, \,3\}\) |

\(A \nsupseteq B\) |

Not a Superset - \(A\) is not a superset of \(B\) |

\(\{1, \,2, \,6\} \nsupseteq \{1, \,9\}\) |

Additionally we can build up structure with some more advanced operations on sets:

Symbol |

Meaning |

Example |

|---|---|---|

\(\varnothing\) |

Empty set \( = \{\}\) |

\(\{1,\, 2\} \cap \{3,\, 4\} = \varnothing \) |

\(\mathbb{U}\) |

Universal Set - set of all possible values in the area of interest |

e.g. \(\mathbb{U} = \{1,\,2,\,3,\,4,\,5,\,6,\,7\}\) |

\(A^c\) or \(A'\) or \(\neg A\) or \(\bar{A}\) |

Complement - elements not in \(A\) |

\(\neg A = \{5,\,6,\,7\}\) \(B' = \{1,\, 2, \,6,\, 7\}\) |

\(A - B\) or \(A \setminus B\) |

Difference - in \(A\) but not in \(B\) |

\(\{1,\, 2,\, 3,\, 4\} \setminus \{3,\, 4\} = \{1,\, 2\}\) |

\(A \oplus B\) |

Symmetric Difference - in \(A\) or in \(B\) but not in both \(A\) and \(B\) |

\(\{1,\, 2,\, 3,\, 4\} \ \{3,\, 4\} = \{1,\, 2\}\) |

\(a \in A\) |

Element of - \(a\) is in \(A\) |

\(3 \in A\) |

\(b \notin A\) |

Not element of - \(b\) is not in \(A\) |

\(6 \notin A\) |

\(P(A)\) |

Power Set - all subsets of \(A\) |

\(P(\{1, 2\}) = \{ \{\}, \{1\}, \{2\}, \{1,\, 2\} \}\) |

\(A = B\) |

Equality - both sets have the same members |

e.g. \(C = \{5,\,3,\,4\},\, C = B\) |

\(A \times B\) |

Cartesian Product - set of ordered pairs from \(A\) and \(B\) |

\(\{1,\, 2\} \times \{3, \,4\} \) \(= \{(1, \,3), \,(1,\, 4), \,(2,\, 3),\, (2,\, 4)\}\) |

\(\|A\|\) or \(n(A)\) |

Cardinality - the number of elements in set \(A\) |

\(\|A\| = 4,\,\|B\| = 3\) |

\(\|\) or \(:\) or st |

Such that |

\(\{ n\, \|\, n > 0 \} = \{1, 2, 3, \dots\}\) |

\( \forall\) |

For All |

\(\forall \,x > 1,\, x^2 > x\) |

\(\exists\) |

There Exists |

\(\exists \, x \,\|\, x^2 > x\) |

\( \therefore\) |

Therefore |

\( a = b \therefore b=a\) |

iff or \(\iff\) |

If and only if |

\(2a = 2\) iff \(a=1\) |

11.2. Definition of a set¶

There are two basic ways to define a set:

List / Tabular Form, where we list the members of the set in any order. For example, the set of all the vowels and consonants:

or the set of the Natural number and Integers:

Set-Builder Form / Property Method, where we state the properties which characterise the elements of a set, i.e. those held by members of the set (but not by non-members. For example:

which we read is “The set \(A\), defined by elements \(x\), such that \(x\) is an integer”. There are many ways to write out such a statement, the simplest is to use the wider notation of set theory. For example, the set of Rational numbers or Complex numbers:

11.3. Venn Diagrams¶

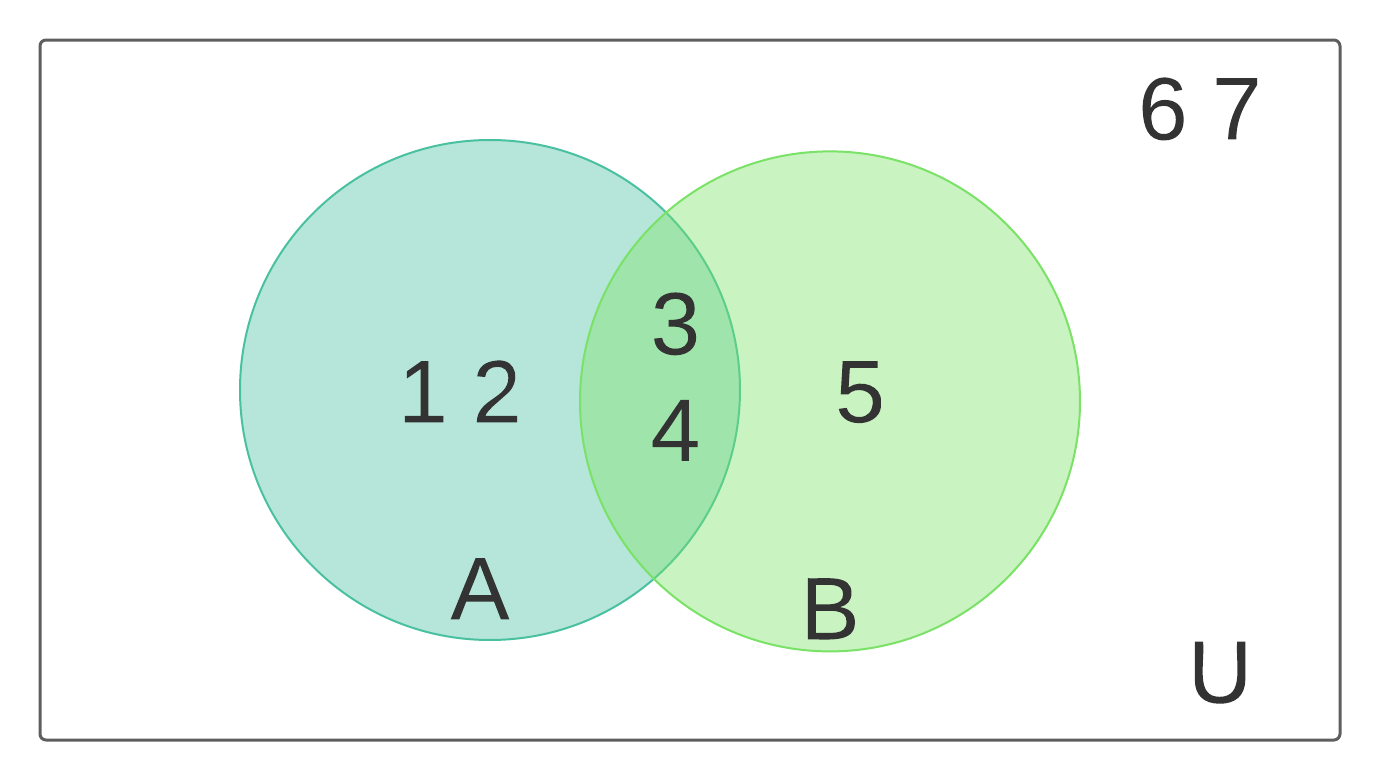

We can represent sets pictorially using Venn diagrams (named after a Logician and Philosopher Dr John Venn, who’s grandfather Rev John Venn has a street named after him in Clapham, South London!), which are an easy to see how different sets can have shared and unique elements as well as defining the Universal set \(\mathbb{U}\) in a given context.

Considering our example of sets \(A,\,B,\,\mathbb{U}\):

this could be represented by the Venn diagram in Fig. 11.1.

Fig. 11.1 Venn diagram depicting sets \(A,\,B,\,\mathbb{U}\).¶

We can see that the union of both sets is given by the entire shaded area

whilst the intersection of both sets is given by the shared shaded area

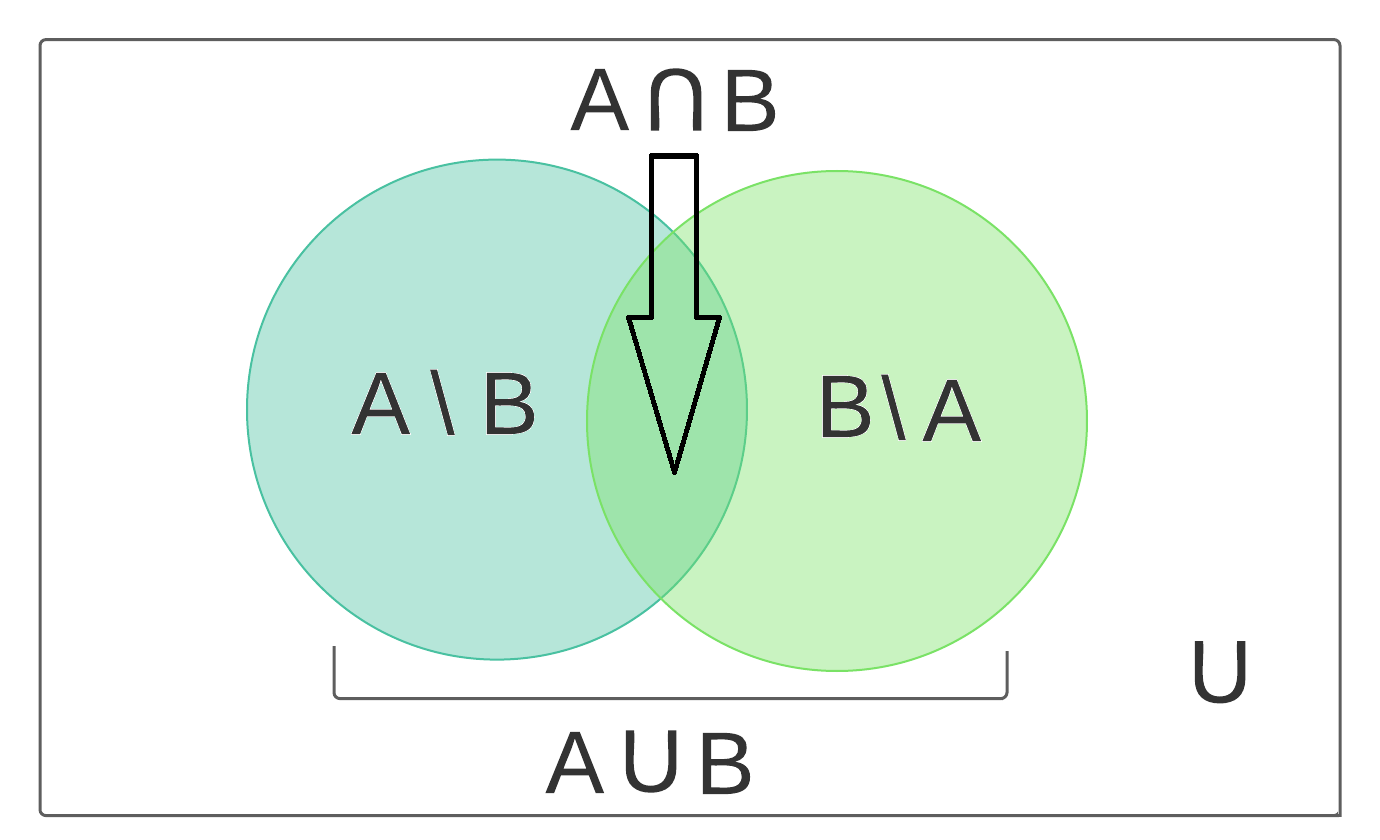

For the difference between the sets,

these could be represented by Venn diagrams, such as that seen in Fig. 11.2.

Fig. 11.2 Venn diagram depicting sets \(A\), \(B\), \(A \cup A\), \(| \cap B\) and \((A\cup B) \setminus B\).¶

and likewise the complement

these could be represented by Venn diagrams with appropriate shading.

11.4. Laws of the Algebra of Sets¶

Sets follow a specific algebra, which we can deduce by following the logical principles outlined previously. There are identity laws, i.e. can we use AND or OR like multiplying or adding on 1 or 0:

Associative laws, i.e. does the position of the brackets matter:

Commutative laws, i.e. does the order of operations matter:

Distributive laws, i.e. does the operation in a bracket expand out:

Involution laws, i.e. is the inverse of the inverse return to the original state:

Idempotent laws, i.e. it’s everything or nothing:

Complement laws, i.e. does everything add up together or subtract to zero:

And finally DeMorgan’s laws, which refer to overall inverse relations:

11.5. Counting Sets¶

It is often useful to count elements within sets and therefore use the logical extensions of these ideas to find the particular areas of shaded Venn diagrams.

If \(A\) and \(B\) are finite, disjoint sets, i.e. \(A \cup B = C\) is finite and \(A \cap B = \varnothing\), then

A simple example of this is

which is simply joining up a set and its complement. One issue with counting elements in sets is over counting, consider for finite sets \(A\) and \(B\):

which is outlined graphically in Figure Fig. 11.2. We can also state this idea as:

where the equality holds if the sets are disjoint and the inequality holds otherwise. To avoid this over counting, we can construct the set \(A \cap B\) and so

We can also extend these statement to many sets, suppose \(A,\,B,\,C\) are finite sets:

where we need to remove the double counting, but in doing so we loose the triple counting, so we need to re-add this total intersection at the end.